A Forbidden Family History: One Man’s Quest to Share His Great Grandfather’s Takedown of a Deadly 20th Century Italian Mob

All families have secrets. My family’s were hidden away in two cardboard boxes, wrapped in blue plastic and secured with packing tape by my father—which in my 12-year-old mind—made them more tightly guarded than Fort Knox. The secrets in those boxes traveled in and out of young life in whispers and snippets, in anecdotes and vague suggestions. Grownup relatives who noticed me listening would get up and leave the room to carry on behind closed doors. Occasionally, at my uncle Hammy’s apartment (he had possession of the secret boxes before he turned them over to my father), I caught a glimpse of yellowed news clippings with sensational headlines; “Inspectors Seize Black Hand Band!” “Federal Sleuths Land Black-Handers,” “Ohio Leads Effort to Rid America of Black Hand Terrorists!” I marveled at antique revolvers and foreboding daggers Uncle Hammy carried up from his basement; old letters in sweeping calligraphy with drawings of skulls and bleeding hearts. I shuddered at mug shots of swarthy men with eyes so dark and menacing they bore right through me.

Every time my father caught my sister or me covertly gathering intel on our family’s secrets, we got the same admonishment: You are never, ever to speak of any of this. Do you hear me?

In bed at night on the second floor of our Akron, Ohio home, I obsessed over the box of secrets. The tidbits I gathered from adults who didn’t know I was listening ripened into wild stories in my head. There were death threats and dynamite explosions. There were stacks of money and unsolved murders. The Black Hand moved in the shadows. Its members had romantic names: Salvatore, Orazio, Ignoffo. The bandits preyed on people like my maternal grandfather Vincent, an Italian immigrant who had a successful business making and repairing leather shoes.

In bed at night on the second floor of our Akron, Ohio home, I obsessed over the box of secrets. The tidbits I gathered from adults who didn’t know I was listening ripened into wild stories in my head. There were death threats and dynamite explosions. There were stacks of money and unsolved murders. The Black Hand moved in the shadows. Its members had romantic names: Salvatore, Orazio, Ignoffo. The bandits preyed on people like my maternal grandfather Vincent, an Italian immigrant who had a successful business making and repairing leather shoes.

The villains were thrilling for sure. But my favorite part of the stories were the good guys— handsome and dapper in white shirts and starched, rounded collars, hair impeccably combed, puffing on fat cigars. They were the U.S. Post Office Inspectors—the world’s greatest detectives of their time and the oldest federal law enforcement agency in the United States of America. In the center of my fantasies was the most charismatic character of all; the legendary lawman John Frank Oldfield—my great-grandfather.

It would be another decade before I understood why my parents were so careful with our family secrets. After Frank Oldfield’s spectacular crime bust in 1909, the Black Hand faded into the 1920s, then ebbed and flowed into the following decades as the mafia, the mob, the syndicate. Techniques remained the same. In the mid 1940s, when she was in middle school, my mother’s job was to open her father’s shop in the mornings. One day, there was a dead man lying outside the entranceway. The man’s face was gone. She knew instantly what it meant. It was a warning to her father: Next time, you better pay, or this will be you.

In the 1960s when my sister and I were very young, the mafia emerged more violent than ever in Youngstown, a booming industrial town in northern Ohio. Celebrity mob bosses had the run of the underworld in Cleveland and Cincinnati, where gambling, prostitution and extortion ran rampant. Attorney General Robert Kennedy promised to stamp out the scourge of organized crime sweeping the nation. For my parents, nothing about it was glamorous or exciting. Many of the same Sicilian surnames of those my great-grandfather sent to federal prison still adorned neighborhood mailboxes. They owned the stores where we bought our groceries and clothes. They were the politicians and senior executives at the country club. Whether a family was still involved in criminal activity, or whether they’d become upstanding citizens— no family in 1970s Ohio wanted to be linked to the infamous Black Hand Society.

Victoria Bruce

My parents’ unease was not enough to keep me from strategizing on how to uncover more details of my family’s history. One day, a stroke of good fortune came in the form of a visit by my uncle Mario and cousin Steve. My mother’s little brother, Mario, was 16 years her junior and more like her own kid than a sibling. He and Steve were like brothers. Like me, Mario and Steve were enormously curious about the Black Hand mobsters and Inspector Oldfield. Unlike me, they weren’t afraid of asking questions. Every time Mario came by (already three sheets to the wind), new details would escape from my mother’s memory over beer and cigarettes at the kitchen table. In the wee hours of the morning, my mother would finally join my father upstairs, and Mario and Steve would sleep on our living room floor. I loved those nights. Neither of them noticed me curled up on the kitchen floor cataloguing every clue.

On one of those visits when I was about 13, I woke suddenly at 3:00 a.m. A beam of light from my parents’ closet shone down the hall and into my eyes. I heard Mom, Mario and Steve giggling and my father harrumphing. I could tell all three of them were inside my parent’s walk-in closet. My heart raced. I knew exactly why they were there. In the very depths of that ten-foot deep closet were our family’s guarded secrets in two cardboard boxes. I lifted my head off the pillow so both ears were available to gather as much as I could from the loud whispers and rustling about. Frustrated and unable to decipher anything of value, I fell back asleep until my father woke me up at 5:30 a.m. He had to leave for work. I had to get going on my paper route.

With my father out the door and my curiosity killing me, I crept down the long hallway to my parents’ room. It was dark, but the closet light was still on. I tiptoed, careful not to wake my mother and hoping to see a snippet of evidence left behind in the night raid.

It was my lucky day.

All over the floor, and all across the taupe carpet were ancient, yellowed newspaper clippings, documents and photographs. Not wanting to get caught peeking into the forbidden treasures, I slowly gathered them into neat stacks. I figured that if I got busted, I could plead I was doing a good thing to protect the priceless artifacts.

William Oldfield

I carefully held each document in my hand and studied it, reading the tiny print. There were deposition transcripts and immigration papers. There were mug shots of young Italians with black wavy hair and scraggly old men with scruffy beards. They seemed to know exactly what I was doing. I imagined them threatening to kill me where I stood. I was scared to death, but I couldn’t stop reading the articles.

A 1909 New York Times article detailed the cracking of the Black Hand case by U.S. Post Office Inspectors: “Fortunately it was the post office Inspection Service, the best detective body in the world, which was put on the case…nothing but the death of the criminal ever takes Uncle Sam off of the case. Time is nothing to him. For a post office detective to spend five years on a mysterious case is nothing unusual. For him to range the entire United States from Nome to Tallahassee is quite customary. His instructions are to get the criminal, and months and miles are no account.”

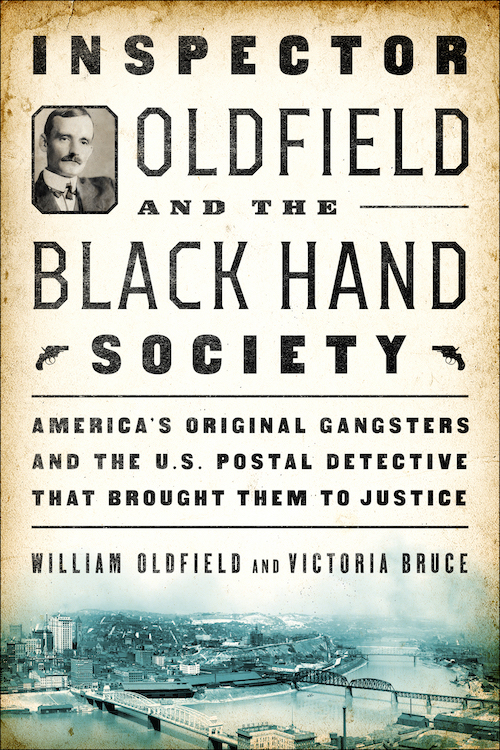

In the center of it all was my great-grandfather, Post Office Inspector John Frank Oldfield. I stared at his photo, a handsome headshot probably taken for some official business; his features sharp, his suit impeccable, his collar bright white and crisp. His arm drapes with cool nonchalance over the back of his chair, his wedding ring prominent on his slight hand. He stared at me intensely—self-assured and bold. And with that look, he challenged me to uncover his story, to investigate the mystery, and to understand how it all came to be. And on that very morning, I took the first step in a life-long journey to uncover the legend of Inspector Oldfield and the meticulous detective work that unraveled the first organized crime syndicate in America.

William Oldfield and Victoria Bruce are the authors of Inspector Oldfield and the Black Hand Society: America’s Original Gangsters and the U.S. Postal Detective Who Brought Them to Justice (Touchstone, August 21, 2018).