Interview: Steven Moffat

(EXCERPTS)

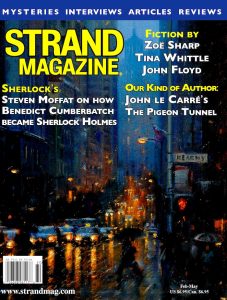

Smartphones, the internet, GPS, and the modern London cityscape don’t traditionally come to mind when thinking of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Victorian detective, Sherlock Holmes. It was July 1891 when the Great Detective first appeared in The Strand Magazine in the short story “A Scandal in Bohemia.” His last appearance, in “The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place,” was April 1927. The enduring success of these stories—and their subsequent adaptations for the stage, film, and television—speaks as much to the chemistry between Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John H. Watson as to the narratives themselves. These two beloved characters have sustained the kind of worldwide popularity that is unrivaled in the annals of classical literature and popular culture. Which is why removing Holmes and Watson from their traditional setting and transforming them into modern men in today’s London would be a courageous act for any writer. Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss undertook this task with Sherlock. The television show finds a young Holmes (played by Benedict Cumberbatch) and Dr. Watson (Martin Freeman) alive and well in modern day London and living at their old Baker street address, complete with computers, smartphones, and all the conveniences modern technology has to offer. First airing in 2010, the show was met with critical and commercial success, and surprised skeptics who had thought everything that could be done with Doyle’s stories had already been done.

Like Mark Gatiss, Steven Moffat grew up reading the Sherlock Holmes stories, and it was while they were writing for the television series Doctor Who that they started trading ideas about a contemporary version. While these contemporary adaptations are not exactly true to Conan Doyle’s original stories, Moffat and Gatiss keep them true to the spirit of the originals, by ensuring that the characters and their relationship with each other are consistent with Doyle’s rendering. Even if “A Scandal in Bohemia” is now retitled “A Scandal in Belgravia” and Charles Augustus Milverton is now Charles Augustus Magnussen, and Moriarty is no longer an older master-criminal mathematician, but instead a young psychopath, and Holmes now uses the internet and text messages to help solve cases, Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss’s Sherlock has further cemented Arthur Conan Doyle’s timeless stories and characters into the psyche of a new generation of fans.

AFG: How have you managed to keep the classic feel of Sherlock Holmes, but move it to a modern era?

SM: The essential thing is that Sherlock Holmes was modern. I mean, when Doyle was having his biggest success with it—when it was in the Strand Magazine coming out on a monthly basis with a new story of Sherlock Holmes—it was a story of a modern young man living in modern London. And that sold it to the people reading it. It felt so vivid. Everyone liked to play the game of him being real. That’s how fresh it felt.

Steven Moffat

Over the years, something odd happened to Sherlock Holmes. He became a period piece, actually during Doyle’s lifetime, as you know. And as it became a period piece, it became something else. It became something slightly grander, more important, and, weirdly, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson got much older. If you read the original stories, it’s perfectly obvious they’re young men. In A Study in Scarlet Doyle refers to Holmes as a student. They’re not in their fifties. And yet, as it became a period piece, they became sepia’d into middle age—Basil Rathbone was fifty when he played it. Jeremy Brett was fifty when he played it. Both fantastic, but both actually older than the character as suggested in the original.

So, I think, when you put it in the modern world . . . Mark [Gatiss] and I always refer to it not as a revamp or reboot, but just as a restoration in which you put him back into the modern world. Not “updating.” You’re putting him back into the same world as the consumer of the story. Then you rediscover something about it. You clear away the fog and our hilarious modern version of Victorian London, which is nothing like Victorian London was, and you have him revealed again as who he was. I think it works perfectly because Sherlock Holmes was not designed to be a period piece. It was designed to be a contemporary story. I would always view it as putting him back where he belongs, which is right now. It’s odd that people make a fuss, in a way, about the updating of Sherlock Holmes. We never mention James Bond as “updated.” He’s a Cold War spy. He fought in the Second World War, you know? Yet, all of [the Bond movies] are set in the modern day. One of the most successful runs of Sherlock Holmes in the movies was Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce in updated versions of Sherlock Holmes. I know that sometimes they were not taken very seriously as movies but they were very popular and it worked. I never questioned it.

AFG: It did work! I love Basil Rathbone. I liked Jeremy Brett, because I thought Brett was a good actor, but at times he played Holmes as very manic, and you don’t feel that from the stories.

SM: I know, but what Jeremy Brett did, I thought very impressively, was find a new way to do it. I mean, once Basil Rathbone had come along he knocked everybody else out of the way and said, “No, this is how you do this.” He was a handsome, sexy, and curious Sherlock, and you think, “Oh, that’s the real one,” and I think in fairness he is a version of the character Conan Doyle would most easily recognize. But what’s an actor as good as Jeremy Brett going to do when the intellectual property had been owned by another actor? He went and scoured the stories and made him into a sort of manic depressive, which is a very, very skewed reading, in a way, but it was very electric and exciting and revitalized the character and allowed him to take ownership of that part. For many people, he is the definitive and never-to-be-bettered Sherlock Holmes.

AFG: What is your favorite Sherlock Holmes story? I know that’s an impossible question . . .

SM: Well, you know, I do have a favorite one, actually, just because of my reaction to it when I first read it, which is the very traditional choice of “The Speckled Band.” I first read that when I was twelve or something. I just thought it was the most exciting thing I had ever read. I thought it was utterly amazing, and I still think it’s jam-packed with incidents and twists. Sherlock Holmes straightens up the bent poker, and there’s a great villain, and there’s a snake, and not one piece of it makes, on any level of inspection, the slightest bit of sense, which is also kind of important to Sherlock. The villain keeps a snake in a safe. He whistles to it to lure it back. He brings it a saucer of milk. I mean it’s just bonkers, but when you’re reading it you don’t doubt a single word, and Doyle’s enormous storytelling risks are on such display there. It’s unstoppable. I couldn’t put it down. But, I love most of them. I don’t think I ever was quite as much in love with The Hound of the Baskervilles as everybody else seems to be. I always got frustrated that Sherlock Holmes disappears for so much of it, because that’s more or less admitting that the plot is so simple that Sherlock Holmes’s presence throughout the story would turn it off too quickly. He’d just walk onto it and say, “Well, it’s not a ghost dog, is it? We’ve just got to look for someone who has the opportunity to own a dog,” and that’s it.

When we redid the story for our version, God, we went into hell when we decided we weren’t going to cheat, and we were going to keep Sherlock Holmes present throughout the story. Because you can’t have Benedict off screen—good heavens! And, I mean, we got into such trouble trying to make that work, because it’s such an obvious answer, you know? It’s not a ghost dog, clearly!

AFG: How did you choose Benedict for Sherlock Holmes? We all know he’s said to bear the physical resemblance to Holmes, but he’s also so effective at playing the character.

SM: I would say he does bear a reasonable physical resemblance to Sherlock Holmes. He doesn’t quite have the nose, but other than that, he’s tall and thin and dashingly handsome in a way that Doyle never ever thought Sherlock Holmes should be but all the Sherlocks who have succeeded have been. And so, belonging to that broad type, he was sort of the coming man—everyone was saying that he was going to be a big star when he got the role. We auditioned him and he is such a fine actor—a brilliant actor—that we didn’t need to audition anybody else. It was obviously going to be him, and obviously that’s worked out for us rather well.

AFG: You’re from Scotland, of course. What is the feeling like for you to be carrying on the tradition of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle with Sherlock?

SM: You mean because Doyle was Scottish?

AFG: Exactly. And you also did the TV series Jekyll based on [Robert Louis] Stevenson’s character.

SM: To be honest, the fact that I share my Scottish heritage with them all isn’t a big deal to me. I never really thought about it. The Stevenson and Sherlock Holmes stories were ones that I always loved. I didn’t know Doyle was Scottish when I was a kid reading those stories. I don’t think I knew he was Scottish until, oh, I must have been in my twenties when I saw that lovely interview with him on film, when I suddenly heard that roaring Scottish accent, not only Scottish but very Scottish.

AFG: So what about your choice of Martin Freeman as Watson? Were there internal debates between you and Mark about putting the moustache on Martin Freeman?

SM: No. I mean, we obviously had that out a couple of times. We took it out and then put the moustache back on, and he grows one for one episode, but, I mean, the kind of man Dr. Watson is would have worn a moustache back in Victorian London and wouldn’t have worn one in modern-day London. That’s just the fact. We decided to update [the stories] properly, and that means that there have to be some changes. In the stories, they call each other Holmes and Watson. Two modern young men just wouldn’t—that’s for public school boys—so they’d have to call each other Sherlock and John. Equally, it’s highly unlikely that someone of John Watson’s type would have a moustache in the modern era, so the moustache went. So, we always decided to do the right thing as far as modernity was concerned.

Other things of detail that are quite important about the original Sherlock Holmes character is that he’s a God-fearing man, and he’s a Royalist. These are impossible character attributes for a modern-day version of Sherlock Holmes. He just wouldn’t be. That’s not what that sort of man does now, so you have to change those things, because the societal norms around those characters to which they conform or rebel have changed so much that the characters themselves are altered by the landscape in which they stand.

For the complete interview, visit our online shop to order issue 51.