Whether picketing for the Hollywood writers’ strike, reminiscing about sketch-comedy roots in a memoir, or delivering Emmy-worthy performances as unscrupulous lawyer Saul Goodman (Better Call Saul, Breaking Bad), Bob Odenkirk commands attention. What may be less well known is his commitment to family and, most recently, a creative pursuit with his daughter Erin, an artist in her own right. Their debut collaboration, Zilot and Other Important Rhymes, was released this fall by Little, Brown & Company. Erin and Bob dropped in (by Zoom) to share a few thoughts on working together, family dynamics, and the creative process.

Andrew F. Gulli: I read the book, and I thought it was fantastic. It has that quality of even appealing to adults. One of my favorite poems was “I Flubbed It.” So how did the whole process start? Whoever wants to jump in on this one.

Erin Odenkirk: It started when we were little kids, when I was four and my brother was five or six, as Old Time Rhymes, which was just a notebook that my dad drew a cover on. He would read to us before bedtime, maybe some Tintin, maybe some Shel Silverstein, maybe some Berenstain Bears, and then after reading a book or two, we would write a poem or two. And it was like a writer’s room—Nate, my brother, would write a line, and Bob would write a line, and I would write a line. And usually, it had to do with something we were into or something that happened that day.

There’s a lot—there’s like 100 something poems in there—and after we were kind of done with that routine, the book stayed on our shelf like a family memento for years. And then I came home at nineteen amidst the pandemic. I had been at college at Pratt in Brooklyn, and I think Bob felt bad for me and felt I had no social life. And for an eighteen-year-old, I was kind of shut off from the world, especially once the class stopped, zoom class. So we started kicking away at making this as real a thing as possible, so at the very least, it would just be like a fun update to a historical family memento.

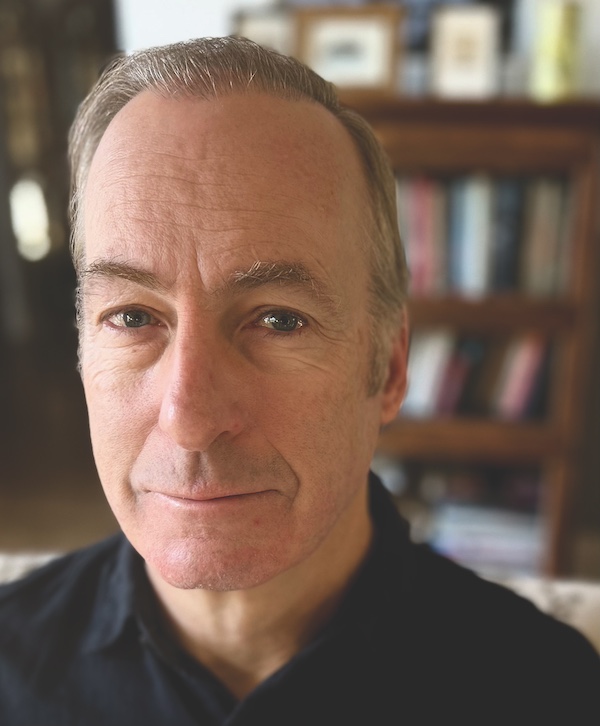

Erin Odenkirk

AFG: So Bob, what’s it like working with your daughter? Was it something that initially seemed like it would be fantastic to do but when it got to nitty gritty, there was conflict between the collaborators?

Robert Odenkirk: Andrew, yeah, you’re smart. You have foresight. I’ve got to say, Erin’s always been a very self-possessed and responsible person, almost to a fault where she has a perfectionism about her that has at times, in her childhood, I think limited her because she just wants to do things perfectly . . . So it’s been amazing to watch her work through that. You can’t be perfect the first time you do anything. You have to allow yourself room to flub it and pick up the next day and start again. So it’s been wonderful to see that she has developed that skill. And that’s great. But I’ll tell you the biggest thing that has been a potential negative. You know, there are things you do around the house, or you make a project together, and it’s really just for the family. But if you say, “Let’s try to take this family thing, that was so warm and that we feel such affection for, and let’s try to turn it into something the world can care about”—you are risking being told no, obviously. And maybe not being “good enough,” not delivering on it. And I sort of am never good at seeing those dangers in the future. So, as we finished, a few months in, and we had about forty poems and we were going to send it out, that’s when it hit me: “Oh boy, I could have set my daughter up for a big failure and a feeling of rejection.” In fact, the truth is the book was rejected the first time it went to publishers, and then we sat down with it and asked ourselves some questions. What was the book? What were the shared themes of the book? What poems were outliers? How can we focus this more? And we went back, and we noticed that the book was about language. The book was about not being afraid to create and write.

So instead of calling it Old Time Rhymes, we used “zilot,” a word my son invented— a word that a kid played with. To [describe] a blanket fort, we’d say, “We’ll build a zilot tonight.” So we perfected our work and resent it. And then we had a bite from a publisher, but in that interim period, you realize you might be setting your kid up for rejection. So you have to be careful, I would say to any parent about taking a home project and thinking of sharing it with the world. I mean, you can learn from failure and you can learn from rejection, certainly, but if a kid’s too young, you might be setting them up for a feeling that they aren’t equipped to make it through.

Bob Odenkirk

AFG: That’s a good point. I know maybe I’m veering a little off topic, but I feel at times that kids are put under a lot more pressure than they were when you and I were kids. And I would say that our generation didn’t have as much pressure as kids do today.

RO: We didn’t have the internet. All that stuff that I did in college, all the comedy I did, you can’t find that anywhere. Thank God! It was terrible, you know? So yes, I think you’re right. There’s a sense that because you can put it on Instagram or what is it, the TikTok thing, there’s a feeling that you must.

EO: And if you do, it also better be liked by everyone. And if it’s not, then something’s wrong with you. And yeah, all of your work could be shared— and that it also should be your best work [laughs] is the philosophy.

AFG: That’s a great point. I wanted to talk to you Erin about this because I looked at your website and I saw your portfolio. I’ve been painting for a long time, and I do a lot of cartooning, and I have to say I was very impressed by the paintings. One of them called Beau was fantastic. And I wanted to talk to you about your illustration style in Zilot because it’s very unique—a bit of Edward Gorey and a little bit of Richard Scarry. It married the bleakness of Edward Gorey with the whimsical nature of Richard Scarry. So how did you develop this unique style of illustrating?

EO: That’s a huge compliment. And I love that on your own you named those two people because they are people that I’ve mentioned when I talk about inspiration for this project. It took a while to find the tone of this book. I mean, I started it when I was nineteen and I have my own style, but I also had this style that I was, sort of like, going for, because I thought it was the coolest and the best, and that’s like Gorey, Burns, Klaus—all of these kinds of darker graphic illustrators. And also having the first draft of the book be called Old Time Rhymes, there was some sense of wanting to evoke printmaking and this sort of older quality of art, like a more ancient art.

And I enjoyed doing that, but it didn’t really fit the nature of the poems which were, at their core, silly and modern, and for a young crowd, like four to eight years old. So when we got that first rejection and had to sort of reconsider things, I took into account things that might be more appropriate for the material we were looking at. And that’s brighter colors, less cross-hatching and shadows, kind of simpler page designs, like letting the whitespace thrive, not feeling like I needed to fill up every single edge and corner. So you’re right in seeing both of those things in there and seeing them sort of balance each other out. That’s exactly how it happened.

AFG: What I found interesting about this book is that—and you know, I’m obviously not from the four-to-eight-year-old crowd—but I thought that some of the rhymes are very funny and some of them are very interesting and some of them, most of them, brought a smile to my face. Or if not a smile, a giggl

e. So how do you manage to write something that can appeal to both parents and kids?

RO: Yeah, it’s a good question. So when I wrote these, I’m with a kid right? There were about twenty-five that were written, you know, in the last three years, but the rest—there’s eighty in total—were written or started when my kids were four or five . . . maybe up till nine. So you have the kids and you’re trying to make them laugh. Maybe it’s a story or subject matter that the kids suggests, and there’s a real interaction and you basically have an audience of one or two. In the case of Erin and Nate, sometimes

it was both kids in the room. And you can try to get them to laugh right there with the next line that you write, or that they write. Naturally, you’re gonna write something that makes you laugh, I think. And the challenge is, don’t make something that just makes you laugh. If the kids don’t get it or they don’t understand why it’s funny, it’s not succeeding. It’s got to work for both. So I’m always thinking in sketch comedy terms, because that’s what I spent twenty-five years writing, and these little comedy poems are a lot like sketch comedy writing. You have a subject matter, you have a concept, and then you twist it and play with it, and then you see if you can find a turn at the end. It’s a lot like a comedy sketch. It’s like having a writer’s room with a four-year-old and a six-year-old.

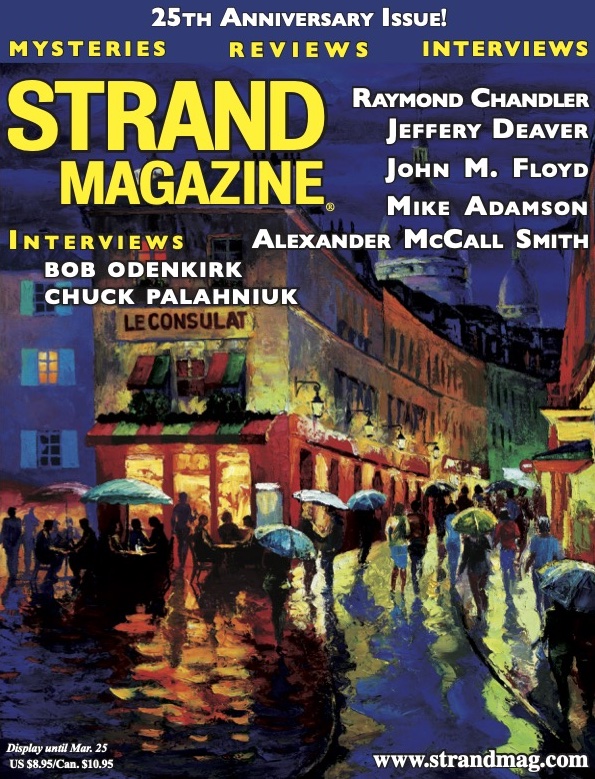

The complete interview is available in our 25th anniversary issue