Over the last two decades, Chuck Palahniuk has established himself as one of the most authentic, intriguing and, at times, subversive voices in contemporary literature. After an inauspicious debut in 1996, his first novel, Fight Club, eventually found its audience, amplifying Palahniuk as a voice for the marginalized, the angry, and the displaced. The eponymous 1999 David Fincher film adaptation of the book helped move the needle from cult following to popular culture awareness. Palahniuk’s subsequent novels—including Survivor (1999), Choke (2001), and Snuff (2008)—have consistently racked up best-seller stats, accolades, and critical acclaim. His works are celebrated for their minimalist style, startling plots, dark humor, and themes rarely tackled in mainstream fiction. Palahniuk was kind enough to join us for an interview, following publication of his latest novel, Not Forever, But For Now, released this fall by Simon and Schuster.

Andrew F. Gulli: This might be a stretch, but when reading Fight Club I was struck by themes which I felt didn’t progress as far as they could in Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground. Mainly, the person who is alienated from society yet has a pathological urge to find meaning in life—which is very contradictory.

Chuck Palahniuk: You’re miles ahead of me on this one. I never think in terms of a person vs. society. My aim is to depict a person who finds power in one way and must find a new source of power as the existing one wanes. In Fight Club, it’s a good boy who follows the rules, but who now finds that being obedient is failing him beyond his youth. He must strike out and find a new persona. The same goes for my book Invisible Monsters, wherein a beautiful woman must find a new form of power as her beauty is lost.

AFG: What did you think of the film version?

CP: I’ve trod this ground so often, I’ll punt here. Loved it.

AFG: You had some very early struggles in life. What ignited that spark to become a professional author?

CP: As a kid who loved books—Encyclopedia Brown, Ellery Queen, science fiction, horror—I dreamed of writing. The safe path seemed to be via journalism, so that’s my degree from college. Even in the eighties the field was overrun, so I wrote freelance magazine articles. My day job was on the Freightliner Trucks assembly line in Portland, Oregon, a job I’d planned to work for a few months, but a job I held onto for thirteen years. All the while I was attending a writer’s workshop on Thursday nights and sending out stories to pulp magazines. My first novel never found a home, but I scrapped out the best bits for subsequent books. Nine years after graduating college I sold Fight Club for $6,000 to W.W. Norton. The novel took years to find a readership, as did the film to find an audience, but all along I’ve continued to write. None of this effort has ever felt like labor. To write is a sustained ecstasy.

AFG: That’s a great line. Do you ever get stuck when you write—what do you do when it doesn’t flow?

CP: Good writing only comes in spurts. Every few sentences I need to fold laundry or walk the dog to let my brain refill.

AFG: My older brother is a huge Jack Palance fan and he’ll kill me if I don’t ask you this: You’re related to Palance—did you ever have a chance to meet him?

CP: My father was so proud of Jack Palance (née John Palahniuk) who’s rumored to be a distant cousin. All I know of Palance is the time he did push-ups during the Academy Awards. More recently I’ve been in touch with his daughter, but ours is an occasional letter-writing acquaintance.

AFG: Your work is very streamlined—as an editor (and as a reader) that’s something I love. Would you say that comes from your experiences as a journalist?

CP: My sparse, fast-paced style does stem from writing for newspapers. But my books and stories also arise from my frustration with reading novels that are bloated and slow. Too often my teachers assigned works from the 19th century, a time when readers wanted long books that could eat up the evening hours provided by the new electric and gas lighting. My goal became to write the type of high-energy plots provided by movies, but to depict the topics that films and television were forbidden to broach.

AFG: I know you’re one of those authors who are incessant rewriters—do you find that the minimalist approach means that every word has to have more weight?

AFG: I know you’re one of those authors who are incessant rewriters—do you find that the minimalist approach means that every word has to have more weight?

CP: When my fellow students and I would present work on Thursday nights, our teacher, Tom Spanbauer, would stop us and make us defend any particular word. He’d seize on a word and ask, “Why did you use such-and-such here?” As students, each of us had to have a valid reason for choosing every word or phrase. What was its purpose? Why had we chosen it over similar words? What did that choice add to the tone of the story? Intention and careful deliberation was paramount.

AFG: You once said that Lullaby helped you cope with your dad’s murder. I lost both my parents; they passed away when I was rather young and I’d be lying if I said that it didn’t color my view of life. Did writing the book and subsequent books create an understanding of the pathological mind and the random nature of ghastly actions?

CP: My ideal reader is someone who is sitting bedside as their most beloved is unconscious and dying. That reader just needs a strong distraction in order to survive a period of intense agony. I want my books to help carry that reader into a near future where the pain will be bearable. The job is not to process and find closure. At that early stage the goal is just to survive without jumping out the window.

AFG: Your work has a tendency to shock readers. Is that your intention when you start out or does the plot just take off and lead to something shocking?

CP: It’s never my goal to shock, but I do fear pulling my punches. If the story naturally escalates to a strong event or idea, I never hesitate to include that. But I never set out to upset readers. I am not a cruel person.

AFG: Are you an outliner? You don’t strike me as one.

CP: To outline seems to weaken my motivation to write. To know where the plot will end bleeds away any desire to execute the story, but I’ll plot as far as the end of the second act. If I can get the ball rolling, then I can stay excited because the natural momentum of the events will lead the story to outcomes greater than I could ever have anticipated. In Fight Club, I knew that at some point the support groups would realize the narrator was a fraud . . . but I did not know that Tyler and the narrator were the same person. The eventual reveal dazzled me.

AFG: Who are some of the authors who have inspired you the most?

CP: Amy Hempel, Denis Johnson, Nami Mun, Junot Díaz, Mark Richard, Thom Jones. I seek out short story collections because stories give me more bang for my buck. For this reason, I also look for stories written for mid-century magazines, the type of fiction that was later used for films and television, Philip K. Dick, Richard Matheson, Rod Serling, Ray Bradbury, Margaret St. Clair.

AFG: This might be a question that’s difficult to answer. What would your top five short stories be?

AFG: This might be a question that’s difficult to answer. What would your top five short stories be?

CP: This is an easy question. My top five short stories are all “This is Us, Excellent” by Mark Richard.

AFG: I’ve been fascinated by the literary crime novel and Choke fits well into that category. To just give a five-second description, the novel revolves around a man who pretends to choke on food in restaurants and relies on Good Samaritans to save him and then sends them letters asking them to pay his medical bills. What inspired that novel? I imagine you sitting in a restaurant getting one of those “what if” moments.

CP: Actually, I was sitting in a car. After my father was murdered in 1999, I fantasized about stopping my car at night and lying alone along a dark road until a police officer would stop to gently check on me. At this very low point of my life, I just wanted an authority figure to coax me back into the world. To tell me, “It’s going to be alright. Everything is going to be fine.” In Choke, the narrator is facing the death of his only parent, his mother, so he’s seeking to enroll the entire world as his surrogate guardians. He wants to be adored and supported by everyone, even if it means continually lying to them.

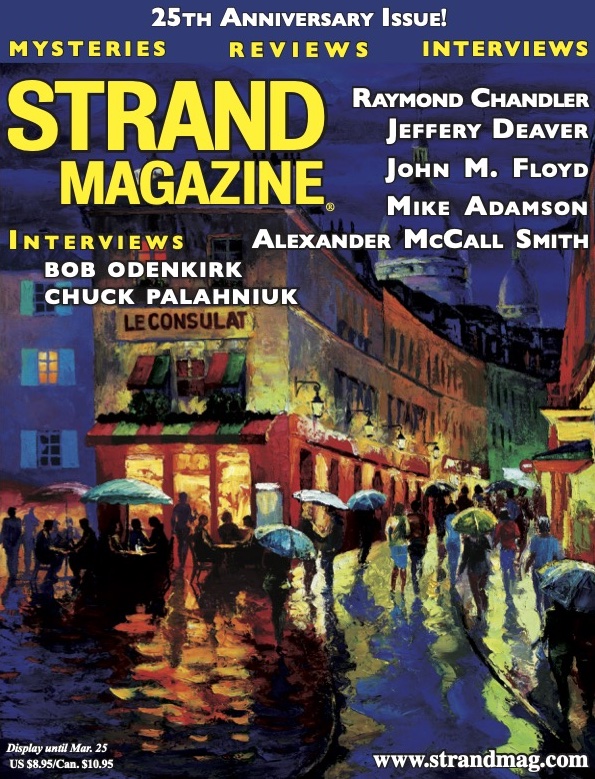

The complete interview is available in our 25th anniversary issue.