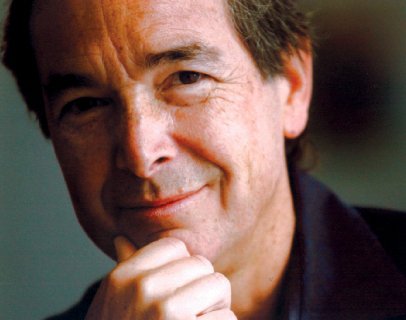

Interview with Martin Cruz Smith

In 1972, Martin Cruz Smith envisioned a novel in which a Soviet and an American detective collaborated to solve a crime. His publisher loved the idea and offered a generous advance. However, after a trip to the Soviet Union, Cruz Smith came home with a different idea: forget the American detective and center the book around the Soviet. Fearing this would be a hard sell, his publisher was less than enthusiastic. Still, Cruz Smith never gave up. Nine years and a new publisher later, Gorky Park hit the shelves, giving the world its first taste of the stoic, ever pragmatic, and resourceful Arkady Renko. The novel drew critical praise for its vivid and realistic Russian setting, well-researched police procedure, and exploration of the Cold War’s shifting complexities. Together with its sequels—Polar Star (1989) and Red Star (1992)—the Gorky Park trilogy is now considered an espionage classic, and, along with Cruz Smith’s subsequent novels have reinforced his renown, enshrining him alongside Len Deighton, John le Carré, and Anthony Powell as a master of the modern spy novel.

While the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 might have contributed to a lapse in the relevance of the conventional Cold War thriller, Cruz Smith’s prescient decision to create a hero from the other side of the pond has paid dividends. As tensions between Russia and the West continue to evolve, the Renko novels have only increased in relevance, with novels such as Wolves Eat Dogs (2004), in which radiation poisoning is used as an assassination method, Stalin’s Ghost (2007), which deals with the circumvention of the democratic process, and Tatiana (2013), a timely tale about the murder of a Russian dissident journalist.

In step with his best-seller status, Cruz Smith’s accolades include a pair of Hammett Awards from the International Association of Crime Writers, a Gold Dagger Award from the British Crime Writers Association, and three Edgar Award nominations. In 2019, he received the Grandmaster Award from the Mystery Writers of America.

Martin Cruz Smith’s latest novel, Independence Square, was released in May by Simon & Schuster.

FG: Tell us about your latest book, Independence Square.

MCS: When I began writing the book, I was transfixed by what was happening in Russia and Ukraine and wanted to write about the period right before the invasion. In Independence Square, an anti-Putin activist named Karina goes missing, and Arkady promises her father he will try to find her. He has broken up with his longtime lover, Tatiana, but befriends a Ukrainian woman who worked alongside Karina. The two of them drive to Kyiv just as Russian troops begin gathering on the Ukraine border.

AFG: Back in the 1980s, after the publication of Gorky Park, the Soviet government labeled you a “graphomaniac,” banned the book, and declared you a provocateur. I’d love to know what the term graphomaniac actually means.

MCS: I don’t think it’s a real word but can assume that a graphomaniac is someone who is so obsessed with writing, he can’t stop.

AFG: You published Gorky Park in 1981, during a very tense period in Soviet-American relations—not as tense as 1961—but still very tense. While it seems plausible today to get a publishing contract for a book with a protagonist from an enemy country, back then it must have seemed, for lack of a better term, a crazy idea. Did the wide popularity of the book surprise you?

MCS: In fact, my then publisher, Putnam, thought the idea of a Russian protagonist was crazy. I had sold them an idea about an American detective going to Russia to help solve a mystery that involved an American citizen.

After I spent a few weeks in Moscow in 1973, I realized what a small idea that was. I wanted to write about Moscow and Russians and to do that I needed a Russian protagonist, not another American cop. My publisher didn’t like this idea at all. He said he would publish my book but without enthusiasm. In other words, the book was dead before I even started writing. I asked to buy back my contract. He refused, so I wrote Gorky Park between other writing assignments over the next ten years, but I put the pages in a desk drawer rather than hand them over to Putnam. In the meantime, the publisher left Putnam and the new publisher let the book go. Random House picked the book up and published it in 1981. I actually don’t think Gorky Park would have done as well as it did if I hadn’t spent nine years writing it because over that period of time, I learned to be a better writer. By the time I finished it, I knew what I had.

AFG: Did you think Arkady Renko was such a successful protagonist because he could see the decay and corruption in the USSR and, at the same time, could see that things on the other side were not all roses?

MCS: Yes, Arkady has scope; he recognizes dishonesty and corruption wherever he encounters it.

AFG: You’ve been very successful in this business for a long time. What do you think is the secret to your long career?

MCS: My longevity is linked to Arkady’s. As long as he remains intelligent, humorous, and romantic, so shall I.

AFG: I’m sure you’re asked this all the time, so I won’t be offended if you refuse to answer this question, but what do you think will happen in the Ukraine?

MCS: It all depends on one sick man: Vladimir Putin. But if I were a betting man, I’d say it’s about four-to-one that the Ukrainians will prevail.

AFG: I tend to think that we may one day wake up and find out that Putin has been declared ill and then a technocrat who is slightly more palatable to the West and to his own citizens will take charge.

MCS: That sounds very likely. It would be interesting to be a fly on the wall and hear what his cabinet is saying about him. I’m sure they’re worried.

AFG: What are some of the things we should know about Russian culture that we in the West are unable to glean from the media and books?

MCS: We in the West tend to see Russia as a somber scene, but it can be as joyful and fanciful as the music in Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf and as light as a pas de deux at the Bolshoi. Also, I am always struck by the Russians’ saving sense of humor. By “saving,” I mean that their humor can dissolve all our dark preconceptions about them and charm us. Chekhov has a saving sense of humor.

AFG: Your dad was a jazz musician and I’m a big jazz fan. I’d love to know who some of your favorites are?

MCS: Jazz was played on speakers in almost every room of the house. It was constant and often drove me crazy, but in my late teens I began to appreciate it. My father played the sax, and his favorite was Charlie

Parker. I suppose he’s one of my favorites too. My father used to follow him around the village in New York and hear him play alone outside in a snowstorm. He also caught him playing in a phone booth for theacoustics.