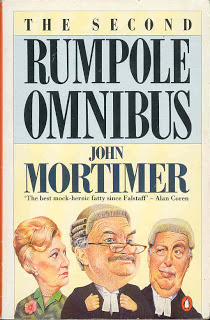

Interview with John Mortimer

(Editor’s note: Rumpole and John Mortimer were to us what Doyle and Sherlock Holmes were to the old Strand. In my 12 years as editor, I have never worked with a writer like John; his sharp instincts, creative genius, and genuine kindness were unparalleled.)

“Both my father and I were guilty of infidelity to the law; my mistress was writing, his was the garden.”

-John Mortimer

Murderers and Other Friends (1994)

Sir John Mortimer’s so-called infidelity to the law has resulted-much to the delight of his fans-in an ever-increasing body of work which includes numerous novels, short stories, plays, and screenplays as well as three very entertaining memoirs-Clinging to the Wreckage (1983), Murderers and Other Friends (1994), and The Summer of a Dormouse (2000).

John Mortimer was born in Hampstead, London in 1923. He attended Oxford University’s Brasenose College, graduating in 1940 with a degree in law. During World War II he served as a scriptwriter and assistant director for the Crown Film Units. His first novel, Charade, was published in 1947. One year later, in 1948, he was admitted to the Bar. Like his father before him Mortimer became a divorce barrister, but after handling divorce cases for several years, he grew tired of dealing with bickering spouses at their worst and turned to criminal law where he found criminals to be a more reasonable class of people. He became a Queen’s Counsel and left behind depressing divorce briefs to enter the world of criminals, jury trials, and Old Bailey hacks. It was in his capacity as a QC that he became acquainted with the kinds of characters and cases that would eventually populate the Rumpole stories.

Despite the success of his legal career, he regarded it largely as a day job “much like waitresing” and throughout those years continued to write prolifically for the stage and screen. He established himself as a successful playwright with such plays as The Dock Brief (1957), What Shall We Tell Caroline? (1958), The Wrong Side of the Park (1960), The Judge (1967), A Voyage Round My Father (1970), and Collaborators (1973). His most successful play is the autobiographical A Voyage Round My Father which gives an honest but affectionate portrayal of life with Mortimer’s eccentric poetry-quoting father, on whom Mortimer’s most famous creation was partially based. A Voyage Round My Father was successfully adapted into an award-winning BBC teleplay and later into an award-winning film starring Sir Laurence Olivier and Alan Bates. He is also the author of several novels-many of which have been successfully adapted for television-including Summer’s Lease (1991), Dunster (1993), Under the Hammer (1995), and a trilogy of novels-Paradise Postponed (1986), Titmus Regained (1991), and The Sound of Trumpets (1998)-following the rise and subsequent fall of Mortimer’s scheming and merciless Tory MP, Leslie Titmuss, that offer an interesting portrayal of British parliamentary politics in which neither New Labour nor the Torries escape unscathed.

However, his most famous creation is the poetry-quoting, cigar-smoking “great defender of muddled and sinful humanity” Horace Rumpole, so adeptly brought to life for television viewers by the incomparable Leo Mckern of whom Sir John writes in Murderers and Other Friends, “Now, when Rumpole speaks in his own voice, it is always Leo’s voice also.” Mortimer has been chronicling Rumpole’s adventures since 1978. His latest collection of Rumpole short stories, Rumpole and the Primrose Path, will be released by Viking Books in December 2003. At 80 years old Sir John continues to write as prolifically as ever. I spoke to him in February, 2002. At that time a new play of his called Naked Justice was due to open in London.

AFG: I’ve enjoyed reading your books for a very long time.

AFG: I’ve enjoyed reading your books for a very long time.

JM: That’s very kind. I think your magazine looks beautiful. I love the old-style magazine.

AFG: What are you working o

n now?

JM: I’m rather busy. I’ve done a couple of plays and I’ve got a play starting on Monday which is about three judges, but I am going to write another Rumpole.

AFG: Well I’m glad to hear that. The last story I read [“Rumpole Rests His Case,” where he has a heart attack] had me worried.

JM: He’s going to recover, like Sherlock Holmes did, and come back. I think he’s recuperating somewhere now.

AFG: So tell me more about the play that’s opening.

JM: Well, you know, in England, judges arrive at a town, and they all live in a house which is kept for them and there are usually two judges-a civil judge and a criminal judge, and a lady judge who does the matrimonial cases, and a trial is going on and the judges are sort of blackmailing each other. And terrible secrets about their pasts emerge. It’s called Naked Justice.

AFG: That sounds fun. And who’s acting in it?

JM: An actor called Leslie Phillips. I don’t know whether you know him?

AFG: Oh, yes. He was in Summer’s Lease.

JM: He was. He did a scene with John Gielgud in Summer’s Lease.

AFG: Signor Fixit! The fellow who was always afraid of getting run over by a lorry!

JM: That’s right.

AFG: I know that you yourself were a QC. Was there ever a person whom you defended who you really looked upon with a horrible revulsion, a person whom you thought, well I’d have been happy if they put him away?

JM: Well you know, the theory is that everybody needs defending-you shouldn’t judge the case before you-and nasty people get beaten in court more than nice people on the whole. But the worst thing is to believe your client has to be innocent. Then you lose all sense of proportion. I mean, if you think perhaps they did it, then you see all the points against you, but you’re not really meant to decide whether they’re innocent or guilty. The only one I really turned away from was a divorce case. The husband was my client and was supposed to have done dreadful things to his wife, but he turned out to be an Assistant Hangman, so I said I wouldn’t act for him. I said, “Get out of here. I don’t want anything further to do with you.”

AFG: I don’t know how anybody can have that job. You know, over here in parts of the United States they do have the death penalty.

JM: Isn’t it awful?

AFG: It really is. And I think that many times innocent people die.

JM: Well, they’re all badly defended by public defenders, aren’t they? And they can’t spend any money on enquiries, expert evidence, or anything like that.

AFG: Yes. It’s not like England of course . . .

JM: . . . where you get the best QC’s for nothing.

AFG: So tell me, Rumpole had a Penge Bungalow case. If you look back at your legal career, which would you say is your Penge Bungalow case?

JM: [He laughs] Well I thought of writing my Penge Bungalow case in the new lot [of Rumpole stories]. I did these, sort of, obscenity cases. There was a case-the Oz trials-which I did in the 60’s when there were all those underground magazines. They came out with a schoolkids’ edition, which it was said would corrupt the young. And that, I suppose, was one of my most famous cases. And I defended a book called Last Exit to Brooklyn. I did all those sorts of books.

AFG: And how about with murders? For example, have you ever gotten a man off whom everybody was pointing the finger at?

JM: Well, I did get a man off whom everyone was pointing the finger at, but after I got him off, I discovered he was a Mafia hitman. [He laughs]

AFG: Well you know, that wasn’t a case you wanted to lose!

JM: Yes! He was found in Soho kneeling beside the dead body. The bloodstained knife was in his motorcar. He didn’t speak any English, so he had to have a girl interpreting for him in Italian. And, I think, they fell in love with each other in the witness box. Anyway, I got him off with no problem at all, but then in the end they told me he was a Mafia hitman.

AFG: What mitigating circumstances did you find?

JM: Well, it was all frightfully clear. He saw this bleeding body so he knelt down and touched him, which was why he got blood all over his hands. Then he found the knife and for some reason thought he’d put it in his car. The jury thought all that was wonderful!

AFG: Did he really do it or do you think ….

JM: Yes, he did. I’m afraid he did.

AFG: Did he get into any more trouble after that or did Brixton prison cure him?

JM: I didn’t see him again. I did a lot of murders but my murders were usually not gangland murders, but husbands’ and wives’ quarrels, lovers’ quarrels, and best friends’ quarrels. I did a Rumpole story about one-“The Tap at the End of the Bath.”

AFG: I remember reading that one.

JM: That was totally true. The judge said, “You know, this cruel woman made her husband sit at the tap end of the bath,” and so he got off. But the judge had never been made to sit at the tap end of the bath!

AFG: That was a funny one.

JM: That actually really happened!