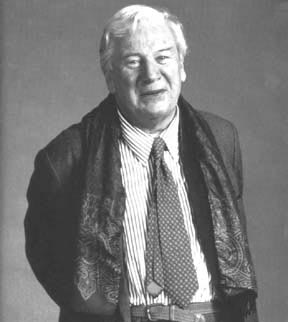

Interview with Sir Peter Ustinov

Editor’s note: Peter Ustinov has been dead for almost ten years, yet his films will continue to entertain millions of fans around the world.

This was the second interview I ever conducted and I has a bit nervous. Having an old, funny, and kind hearted pro like Ustinov at the other end put me at ease and after a few minutes it just turned into a long and wonderful conversation. My next interview was with an angry Kurt Vonnegut and lasted only five minutes—let’s not go any further!)

Sir Peter Ustinov is a man of many talents. As an actor, playwright, director, producer, writer, and set designer he has used those talents to entertain and enlighten audiences the world over. He remains an eloquent and tireless voice for world peace and understanding between nations. For the past 31 years he has served as ambassador-at-large for UNICEF.

During his long and distinguished film career, Sir Peter has played a variety of characters including the Emperor Nero (Quo Vadis?, 1951), King George IV (Beau Brummell, 1954), Lentulius Batiatus (Spartacus, 1961), Captain Vere (Billy Budd, 1962-the critically acclaimed film which he wrote, produced, and directed), and the roguish Arthur Simpson (Topkapi, 1964). He received Academy Awards for the roles he played in both Spartacus and Topkapi.

He is an accomplished playwright as well. His first play, House of Regrets, was produced in 1942 and received splendid reviews. In the years that followed, Sir Peter has written several more successful plays including The Love of Four Colonels (1951), Romanoff and Juliet (1956), Photo-Finish (1962), The Unknown Soldier and His Wife (1967), and Beethoven’s Tenth (1985). In addition to acting in, producing, and directing some of his own plays, he has also directed various operas.

He has also written several books, among them The Frontiers of the Sea (1966), Add a Dash of Pity: and Other Short Stories (reprinted by Prometheus Books, 1996), Krumnagel (1971), and Life Is An Operetta: and Other Short Stories (1997).

In 1968 he was elected Rector of Dundee University and served two terms of three years each. In 1990 he received a knighthood and since 1992 he has served as Chancellor of the University of Durham. His latest novel, Monsieur René, has just been released by Prometheus Books. We discussed a wide variety of subjects including his many interests and accomplishments, his impressions of the actors and directors he’s worked with, playing the part of Hercule Poirot, writing, his work with orchestras, and the state of the world-past and present.

TSM: To start, you have a new book due to come out called Monsieur René. What is it about?

USTINOV: Well, it’s my fourth novel and it takes place in Switzerland. It’s not really a mystery; it’s a kind of antidote-to-Lolita love affair between two elderly people, quite apart from anything else. The hero is a man who has reached what he imagines to be the end of his active life. He’s retired and he’s the life-president of the International Brotherhood of Hotel Porters and Conciérges and, as such, very respected in his own milieu. Like many people who have been brought up in a very strict religious ambience, he believes the biblical life-span as being a rule, which is seventy years-in other words, three score and ten. And so at the age of seventy he suddenly finds himself on borrowed time and beginning to question all the things which have made his life important. He wonders whether his life was really as admirable as all that. What does it entail? It entails being friendly and helpful to some of the more despicable people alive today who can afford those kind of hotels, and always refraining from looking in his palm too soon in order not to risk registering displeasure at the amount of the tip. And he suddenly begins to feel that the whole hotel business could be put to a much more active use, especially in this age of information which he feels creeping up on him. So he tries to organize a kind of information grid-for which the hotel is admirably suited. He wishes that waiters would no longer interrupt to ask if any more vegetables are required. Instead, he wishes they would listen a bit more because they could pick up some very useful tips-especially in a town like Geneva which is full of foreign congresses and suspicions and all sorts of underhanded and yet pleasurable devices. But, unfortunately, the people he recruits are people of his own age who are really not very adapted to that kind of thing, although they enjoy the sense of adventure. Eventually a woman becomes the only extremely active and brilliant member of the organization (she is a housekeeper in a hotel) and they manage to arrange a coup, which of course attracts the attention of the police. The police are another element in the story. This is quite interesting-especially in the Switzerland of today-because it harks back to the Nazi days without commenting on them at all. I’ve always felt it is a little difficult to accuse the Swiss of things when they were the only people with territory touching Nazi Germany who were not in combat.

TSM: During the war you worked with Eric Ambler. What are your memories of him?

USTINOV: They are rather incoherent. He wrote much better than he spoke. But that is true of many people. He was perfectly pleasant about me in his book.

TSM: Here Lies.

USTINOV: That’s right-which I suppose he meant as a double entendre, “here tells lies.” But I think he was very generous to me in his autobiography, which surprised me because at the time it was very difficult because we were all in the army. He was a major and I was a private and it was an uneasy collaboration because he took the military rather more seriously than I did.

TSM: When did you first decide to become an actor?

USTINOV: I think my mother decided for me, because I was quite incapable of passing any exams. I’ve never passed any exam in my life really, except entrance exams into schools. I’ve never gotten any diplomas or degrees and now I’m chancellor of a university! So, when I was inaugurated into the university, in Durham Cathedral, I was able to say how glad my father would have been to see that I had scraped into a university at last. I saw all of the professors look at each other in alarm in the dark. But it was too late.

TSM: Your father also encouraged you to join British Intelligence. What was that like?

USTINOV: I failed that exam, too. And I failed that exam with a result which gave me great confidence in my future. They said they didn’t think I had the kind of face which could lose itself in a crowd. I was lacking in anonymity.

TSM: Do you think you would have made a good spy?

USTINOV: I think absolutely dreadful. First of all, I hate listening to other peoples’ conversations. I think it’s usually one of the most boring activities you could imagine. Spies irritate me enormously, even those I came across during the war. I was so unimpressed with them. Mark you, I was only a schoolboy, but there was one especially-who came to our house puffing a pipe and said he had contact with the German underground movement-whose reasoning seemed to me (when I was only 14 or 15) absolutely cretinous. He was the first prisoner taken by the Germans during the war. He fell into a trap. I wasn’t a bit surprised.

TSM: This is a mystery magazine so I must ask you this- what was it like playing Hercule Poirot?

USTINOV: If you treat it strictly as a character part, I enjoyed that tremendously. But he seems to get kicks in life out of lip reading at 200 yards and I’ve always required something more solid than that. Also he’s a confirmed bachelor, which I’m not, having been married three times. He’s never risked it. He prefers to be pernickety about his crème de cacao, or whatever he drinks after lunch.

TSM: What was your favorite Poirot film of those that you took part in?

USTINOV: I think the best one was the first one.

TSM: Death on the Nile.

USTINOV: Yes.

TSM: In your autobiography, Dear Me, there is a very funny passage about an important meeting that took place in 1938 in your parents’ apartment and your father’s attempts to get rid of you for that evening. What was that meeting all about?

USTINOV: He sent me to the movies and it was more expensive than the last time he’d been-it had increased in price. It was a meeting between members of the British General Staff and the German General Staff. The Germans were trying to make the British stand firm in Munich because they said if they didn’t stop Hitler then, it would be practically impossible afterwards. It’s very indicative of a very active feeling against Hitler at the time. It wasn’t all plain sailing for him-he just had enormous drive and enormous acumen. The world hadn’t really seen anything precisely like that before and I can never blame people for not realizing how serious it was, although I myself did realize it. I was in an English school and spent my holidays visiting my grandmother in Berlin. Nobody would believe the stories I told when I got back. The British had their heads deep in the sand.

TSM: Isn’t it true that Major Stevens, who took part in that meeting, was arrested by the Germans a few weeks later?

USTINOV: He’s the spy I told you about before. I didn’t mention his name. It’s come out again in the papers as all these documents are being dug up. There were two of them-Stevens and another guy whose name escapes me now. But it was Stevens, whom I met, who smoked a pipe and left traces of it everywhere.

TSM: So Stevens was the one at the meeting who didn’t think that the Germans were sincere about wanting to stop Hitler when in fact they were. Then he was duped a week later and arrested in Holland.

USTINOV: Duped is the word!

TSM: You worked with Charles Laughton and Laurence Olivier in Spartacus. What were they like to work with?

USTINOV: Oh, Laughton. I always said he was always hanging around to be offended. He was extremely sensitive and extremely vain, and extremely good. But he always deferred to me because I wrote all those scenes in Spartacus with him at the request of the studio because he wouldn’t play what he was given. He was annoyed, I think, because we had all been given scripts which turned out not to be the real one when we got there. And Charles always [mimicking Laughton] used to refer to me as the Crown Prince, which meant of course he was King. However, one forgave him a great deal because he was really very good at what he did.

TSM: I read in your autobiography that you were in essence the buffer between him and Laurence Olivier.

USTINOV: Yes, I was. For some reason-like animals-they just didn’t like each other. When you get two dogs that growl at each other, you don’t really ask why, you just accept it. But Olivier knew that Laughton was going to appear at Stratford in England as King Lear and tried to make up for this atmosphere by giving Laughton a little diagram with crosses on it and saying [mimicking Olivier], “Dear boy, I’ve marked here the areas on the stage from where you can’t be heard.” And Laughton was delighted. [mimicking Laughton] “Thank you so much, Larry. I shan’t forget that. Oh, you are kind.” And as soon as Olivier was out of earshot Laughton turned to me and said, “I’m sure those are the very areas from which you can be heard.” So there was really nothing to do. But I wasn’t foolish enough to suggest that they should think again.

TSM: I read a very funny passage in your book about how during the war you were once transferred to a psychiatric hospital.

TSM: What are your memories of the film We’re No Angels with Humphrey Bogart and Aldo Ray?

USTINOV: I’ve always said that if I’d known that Humphrey Bogart would become an icon, I would have watched him more closely. But he was just somebody I met every day with great pleasure. He said about the director [mimicking Bogart], “You’ve gotta watch him. He’s got no sense of humor.” In point of fact Curtiz, the director, had one extraordinary drawback. He had been in America for a very long time, but had never really learned the English language. At the same time, he’d forgotten Hungarian and sometimes you just didn’t know what he was talking about. I didn’t know so much on that film [We’re No Angels] because we really made up our own thing-and working with Bogie and Aldo Ray was great fun.

TSM: It was a charming film.

TSM: I have one final . . . it’s not really a question . . . but in your autobiography you wrote something to the effect that people are imprisoned in their minds and that it is our duty to furnish our minds well. Would you like to expound upon that?

USTINOV: Well, I’ve said something else since then. I said I’m beginning to believe in the immortality of the soul, not on any religious grounds at all, but simply because it seems quite clear as you get older that the soul and the body start drifting apart. And I suddenly had a vision of going to a counter, which might be described as a Hertz-Rent-a-Body counter, and asking the girl, “Excuse me, do you have anything with a slightly more powerful engine? Ooh, and with a sliding roof, I’d really like that!” and she says, “No, I’m afraid we’re all out. Either take what we’ve given you or that’s it.” “Oh, I’ll take it, I’ll take it.” So you’re stuck with a body which you may not necessarily feel entirely in concert with. You live with this body throughout your whole life, accommodating it, and of course adapting to it, and then it begins to creak and you hear noises from the back axle, and towards the end you begin to think, “My God, I hope I’ll have the strength to bring this body back to the counter with dignity and not have to leave it out in the countryside with a red triangle behind it.” It’s for that reason I say we’re prisoners in our own shells and the main thing is to furnish them properly.

TSM: Besides all the things that you do, what do you do in your free time?

USTINOV: [speaking with a southern accent], Well, I talk on the phone to people from the middle-west. I doodle. I do all sorts of things. I illustrate books of my own, and I’m just very inquisitive about everything still.

TSM: Thank you so much for this opportunity to speak with you. It’s been very entertaining and very interesting.