The Usual Suspect by Jeffery Deaver

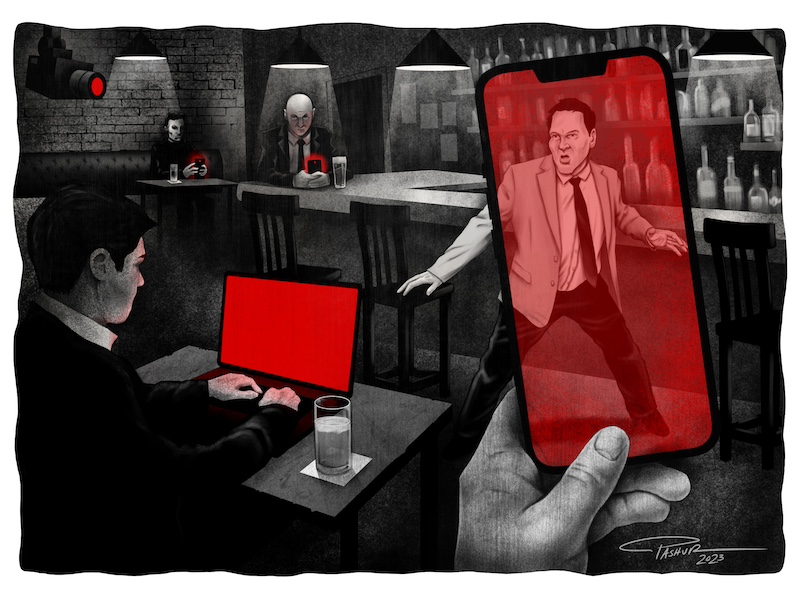

Ted Evans typed the last line of what he’d just written and scrolled through the document once more.

Good.

Still, his finger hovered over the return key, which, when pushed, would send his blog into the ozone for a hundred or a thousand or a million people to read.

This particular one would probably be on the hundred-thousand side, as it had to do with politics and was about a particularly controversial congressman from the Mid-Atlantic state where the blogger lived.

He debated only a moment longer and hit the key.

He was a lean man who didn’t drink alcohol and—heaven forbid—never smoked. His balding head was suntanned, as he was a runner and kept his body in top form with daily outdoor workouts. Part of this was because he occasionally blogged on health issues and wanted to know whereof he spoke, and part was due to his wife’s good-natured pressure to stay fit.

Presently he was in the den of his house in Henderson City, referred to often as “historic,” though every burgh in this quasi-rural part of the state could make that claim, since the counties were settled in the 1600s. His view was of the rose garden he loved to tend. He spent much time there and had the puncture wounds to prove it. He had considered, and drawn no conclusion about, the question as to why rose thorns were so vicious. What in the natural selection process had caused that twist of evolution? Did wolves or other fierce beasts have a taste for the petals?

It was late morning and Evans would soon go for his second breakfast. Always busy, he would wake at five a.m. and put the finishing touches on the blog he’d written the night before. He usually had only a piece of whole wheat toast and coffee as a wake-me-up. Now, at eleven, would come the real thing. Eggs and bacon today. Scrambled, he’d decided.

Before he went into the kitchen, though, he hit the comment section of the blog post he’d just uploaded.

Nothing yet.

Then, email.

A dozen were in the queue.

He read them fast, sent some to Trash, some to Archives.

Some he answered.

Finally, he came to one whose address was an anonymous server. He opened and, frowning, scanned it carefully.

This one Ted Evans didn’t store or deep-six somewhere in his computer.

He printed it out.

And called the police.

Fishing.

Fishing.

This was Detective Patrick Mitford’s approach to policing.

Sitting in his immaculately ordered office in a pen of the State Police’s Major Crimes Division, he looked over the files of the cases he was presently running, the way a fisherman eyes the ocean and decides where to cast his net.

Mitford tugged up his white shirt cuff and, with a fountain pen, jotted a note on a pad of paper. Then another. More reading, more notes.

The detective, mid-thirties, was known for his precision, as witnessed, for instance, in his impeccable clothing. Pressed navy slacks, a starched shirt that had been ironed to perfection, polished black wingtips. His sport coat—beige tweed—hung on a hanger, unlike the jackets of his colleagues, draped unceremoniously on hooks or the backs of chairs.

He was not a big man—slim and below five feet—but he didn’t need bulk to get confessions or close cases.

He fished.

Casting the net, seeing what he caught.

Among the creatures presently in his nets, the biggest perhaps was Charles Whitmore, an investment banker who was also, Mitford was convinced, a money launderer—perhaps the biggest on the East Coast. He was scrubbing money for organized crime figures from Florida to Maine (the latter state as rich a source of oxy and fent as lobsters and Stephen King novels). The businessman had appeared shocked when invited down to headquarters to sit for an interview, during which Mitford inundated him with questions about various transactions he’d engaged in.

“But I don’t get it, Detective. Why me?”

Because I’ve been doing this a long time, and I have a feel for who’s good and who’s bad.

Then there was the second biggest case, the hired killing, a hit. A wannabe mafia boss, Eddie LaPlaya, had ordered the murder of a budding drug kingpin. The victim had died when his apartment burned. It might have been an electrical fire, but Mitford believed it was arson, set to murder the rival. He had no evidence, but, once again, he invited LaPlaya to his office and shotgunned questions his way.

The other cases were a warehouse burglary, a domestic terror attempted bombing, a kidnapping, and a case of bribes going to as yet unidentified state officials.

Lots of sea creatures swam beneath his dinghy.

He was pleased at how all the cases were going—each according to his fisherman’s way, a unique approach to law enforcement, Mitford believed. He would identify someone who might logically be a suspect, bring them in and question them, watching them bluster or quake or frown in confusion or glare defiantly, and then let them go.

The guilty ones would slink back to home or office to destroy evidence or intimidate potential witnesses, in which case Mitford had them.

“You’re under arrest for obstruction of justice . . .”

It didn’t matter if he couldn’t hang them out for the underlying crime. Tampering with witnesses or evidence was almost as serious and resulted in long prison sentences. The ad fish was removed from circulation.

And if the target was in fact innocent, so what? They’d have a few sleepless nights, some embarrassed explanations to neighbors as to why the police were at their doorstep. Even if someone complained to brass, Mitford could deal with that. And besides, a little grief was worth the price of a conviction.

As he was jotting down more questions to pose to the suspected money launderer, he looked up to see Dmitry Cosgrove, his captain, in the doorway. The fifty-year-old was scruffy, looking just like the slightly overweight street cop he’d been years ago. He held a stubby dark brown cigar, unlit. He carried it around always. Like a baby’s pacie.

“Yessir?” Mitford’s straight-arrow, regimented attitude set fellow officers’ teeth on edge; he persisted with ramrod-straight posture and crisp bearing.

“Got something different for you, Mitford.”

“Yessir.” He perked up at this.

The word “different” was often synonymous with two concepts: “not boring” and “career-boosting.”

The captain continued, “There’s a blogger got a threat. He’s supposed to stop writing about something. Otherwise this guy’s threatening to kill him. Theodore Hewlett Evans. Henderson City. The blog is the T.H.E. Report. Get it? His initials.”

Mitford had never heard of him, but then he didn’t follow the papers or TV news much, and never blogs. When he went home at night, he had dinner with his wife and spent the rest of the evening casting nets. He never heeded his wife’s warning that he was overworked, burnt out, and would eventually succumb to mental exhaustion.

“Now, okay? It’s a priority. HQ, they’re leaning on me to jump on it, and close it fast.”

“HQ’s involved?” This was different indeed.

“Yeah, they’re afraid if this guy gets tapped, there’ll be bad national press—you know, we’re not protecting journalists, First Amendment, all that.” He scowled. “Like a dead reporter’s worse than a dead somebody else. But not for me to question. Get on it now, Mitford, and keep me posted.”

Tatiana Ruskov, the bright-haired assistant in the detective pen, stepped into his office and handed him the printout of Theodore Evans’s blog.

Though she was virtually the opposite of everyone in the department—she wore frilly dresses, had her hair carefully coiffed and face artfully made up, and hardly knew one end of a Glock from the other—Tatiana had a fascination with their work, Mitford’s in particular. She often volunteered to help him research his cases and, on her own, she would organize his desk and credenza. And happily retrieve documents from the printer, even when he hadn’t asked her to. Like now.

“You read blogs?” he asked.

“You read blogs?” he asked.

“I like podcasts. You know, when I’m cooking or jogging or driving. But reading? Not so much.”

He’d grunted thanks, picked up the pages, and read the particular post titled “The Unknown Risks of Artificial Intelligence in Corporate Environments.”

Mitford had known very little about AI before reading it. But he’d found the three-page story strangely interesting. It explained clearly, how “large language models,” software programs, sucked up (or “scraped”) information from every source that existed on the internet. These LLMs would analyze the data, then would answer questions posed by users, create documents, and solve problems as well as any human could. Sometimes even better.

Evans’s blog was about the dark side of AI, explaining how these models were becoming too smart too quickly. Even the developers didn’t know exactly how they worked or what they might do on their own. The blogger called for them to slow down the proliferation of LLMs to give experts more time to analyze the risks they posed. He also thought the government had to begin regulating them immediately.

The particular danger was that corporations were using the super-smart LLMs to dodge regulations, undermine competition, and exploit consumers, in ways that could often be undetected.

“Large language models are like unseen killer viruses, rendering datamining nothing more than a common cold.”

Tatiana appeared in his doorway to tell him that Evans had arrived. He told her to show him up, then asked, “You know anything about AI?”

She said, “I use ChatGPT. Helps me write letters.” She was born in one of those Slavic countries and occasionally stumbled with English. “Oh, and I used this one program to draw a picture of me playing tennis with a penguin. It was pretty good.”

Penguin, Mitford reflected. “Go get our guest, would you?”

The full story is available in issue 25 of the Strand