“I first heard Personville called Poisonville by a red-haired mucker named Hickey Dewey in the Big Ship in Butte. He also called his shirt a shoit. I didn’t think anything of what he had done to the city’s name. Later I heard men who could manage their r’s give it the same pronunciation. I still didn’t see anything in it but the meaningless sort of humor that used to make richardsnary the thieves’ word for dictionary. A few years later I went to Personville and learned better.”

This is the opening paragraph to Dashiell Hammett’s first novel, Red Harvest, and I don’t know if establishing a novel’s setting has ever been done better, or in a more ingenious manner. Take another read through this paragraph. Not a single word is used to describe Personville. There is not one adjective. Not one colour, not

one scent. And yet . . . .

You already have a sense of this town, the foreboding and dread that will await you on every street, back alley and nightclub. Without one descriptive word or passage being used to accomplish the task.

Hammett managed to pull off this rather marvelous trick because he never treated “setting” as something secondary to his story. For Hammett, and the noir writers that would follow him – Chandler, Cain, Macdonald – setting was used as another character, quite often, a main character.

Hammett managed to pull off this rather marvelous trick because he never treated “setting” as something secondary to his story. For Hammett, and the noir writers that would follow him – Chandler, Cain, Macdonald – setting was used as another character, quite often, a main character.

It wasn’t a blue sky. It wasn’t the smell of bacon sizzling on a grill in a downtown diner, Setting was the in-your-face monster that was going to decide your fate.

Among the many genre-busting writing lessons of the classic noir authors, place-as-character is often forgotten. It’s easy to understand why. The other lessons — murder is not a parlour game; adverbs are worse than watered-down whisky; style is as important as plot – were so damn good.

But place as character is a lesson worth remembering. If you have any doubts, read the rest of Red Harvest, what may be Hammett’s best book. (Perhaps that’s going too far. Let’s say it’s a tie with The Glass Key.)

While Red Harvest is downright in-your-face about making the place- as-character argument, some other classic crime novels are more

subtle, but just as effective. A good example is The Executioners, by John D. MacDonald.

This novel (perhaps better known by the title Hollywood gave it, Cape Fear) tells the story of Sam Bowden, a small-town lawyer who witnesses a brutal rape. He testifies against the rapist – Max Cady – who is then sent to prison for 14 years, every minute of which Cady spends plotting his revenge against the eyewitness who put him

behind bars.

When Cady is released, he travels to the fictional town of New Essex to exact his revenge. The Executioners is a dark, psychological thriller– one of the darkest of MacDonald’s many novels – and the suspense is ratcheted a slow and painful quarter-turn by quarter-turn.

The setting is essential to the pace and building tension of the story. Bowden – again, a small-town lawyer – tries to defeat Cady by legal

means. He contacts the police once his family begins to be harassed. He tries to hide his family. He tries to run.

But to no avail. To defeat Cady, Bowden must become a criminal, must become no better (well, almost no better) than his tormenter. The transformation is chilling, the ending a shock, and had the story unfolded in a large city, without the quiet, almost pastoral innocence of New Essex, the effect would have been muted, the suspense greatly

diminished.

In a strange twist for a story that had many, we don’t have to guess about this. We have the proof.

There were two film adaptations of The Executioners (both re-named Cape Fear). One was in 1962, directed by J. Lee Thompson and featuring Robert Mitchum as Max Cady. The other was released in 1991, directed by Martin Scorsese, with Robert De Niro as Cady.

The 1961 movie was more faithful to MacDonald’s story, including the small-town vibe of New Essex and the slowly building suspense of Cady’s revenge against Bowden and his family.

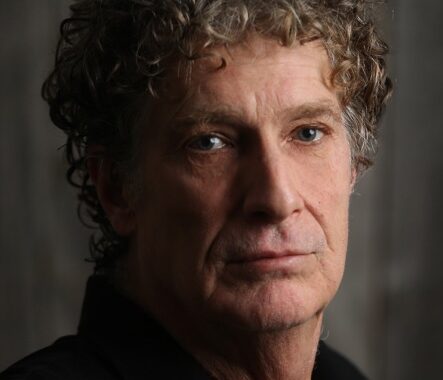

John D. MacDonald

The 1991 movie on the other hand was – something else. What you may remember best about Scorsese’s Cape Fear was De Niro tattooed from head to toe. The small-town feel of New Essex was nowhere to be found in this movie. Indeed, this movie could have been parachuted anywhere into the American South, cameras start rolling, it wouldn’t have made a difference.

Robert De Niro with tattoos. That’s what people remember about the second film adaptation of The Executioners.

critical response to the two movies? The 1961 movie – with small- town New Essex and Mitchum as Cady — has 97% positive reviews on Rotten Tomatoes. The 1991 adaptation has 76% positive reviews.

Roger Ebert’s review of the 1991 movie would have been considered positive (three out of four stars and a thumbs up) and even he said of the movie’s setting and overall feel “(It has) an off-putting and distracting carny show element.”

Yes, it sure did (and I’m a fan of both Scorsese and De Niro).

Setting can be a powerful tool for the mystery writer, as both MacDonald and Hammett have shown us. If you can make it a character in your story, you’re onto something.

And in case you’re wondering (don’t know why you would be, but in case) Hammett knew exactly what he was doing with place and setting when he wrote Red Harvest. Here’s a couple lines from much

later in the novel:

“This damned burg’s getting me. If I don’t get away soon, I’ll be going

blood-simple like the natives.”

If the above lines sound familiar to you – your last, fun Hollywood fact

– this is indeed where the Coen brothers got the title for their movie

Blood Simple.

About the Author

Ron Corbett is a writer, journalist, broadcaster, and cofounder of Ottawa Press and Publishing. A lifelong resident of Ottawa, Ron’s writing has won numerous awards, including two National Newspaper Awards. He has been a full-time columnist with both the Ottawa Citizen and the Ottawa Sun. He is the author of seven nonfiction books, including Canadian bestseller The Last Guide and the critically acclaimed First Soldiers Down, about Canada’s military deployment to Afghanistan. The first book in his Frank Yakabuski Mysteries was nominated for the Best Paperback Original Edgar®