Revisiting Paris: The Story Behind Ernest Hemingway’s Previously Unpublished “A Room on the Garden Side”

Fans of Ernest Hemingway books well know the importance of Paris to his work. Arriving in the “City of Light” in late 1921 along with his new bride, Hadley Richardson, the aspiring writer immersed himself in the Left Bank’s expatriate community of artists and wordsmiths intent on reinventing literature. Under the tutelage of two very different teachers who couldn’t stand each other—Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein—Hemingway learned the importance of le mot juste (“the one and only correct word to use”) and rhetorical effects such as rhythm and repetition. Renting a studio workspace in the hotel where Paul Verlaine died, he set about paring sentences to their absolute core in a series of observational exercises he called “Paris 1922.” The precision and exactitude he achieved in these prose miniatures of the city formed a new style of storytelling he plied in a subsequent series of vignettes on war and bullfighting dubbed In Our Time, which he then expanded into his first short-story collection. From there it was a short hop to The Sun Also Rises (1926), the quintessential novel of Americans abroad and adrift. As critics correctly predicted, Hemingway’s emotional understatement and hardboiled dialogue were so infectious, his peers from here on out would struggle not to sound as if they imitated him, consciously or not.

Thirty years and three wives after Hadley, an aged Hemingway returned to Paris to re-explore its influence on his artistry. Ailing after years of alcoholism and physical injury—including two airplane crashes in Africa on two consecutive days in early 1954—he was, in effect, searching for the moment it all went wrong. Despite at least four classic novels among the seven he published in his lifetime, along with a couple dozen groundbreaking short stories and a little acknowledgment known as the Nobel Prize, the pervasive perception was that Hemingway had become a cartoon. His once revolutionary style now sounded stunted and repetitive; even worse, the values of personal integrity and “grace under pressure” his work promoted now appeared windy and self-aggrandizing—the tiresome bragging of the loudest guy in the room. Remembering how he first became a serious writer, Hemingway started writing about how it was, tapping into a vein of nostalgia and regret that was both sentimental and self-excoriating. While settling some scores against former allies like Stein and F. Scott Fitzgerald, he also took himself to task for not sticking to the principles of discipline and craftsmanship that led him to his literary breakthrough decades earlier. He also raked himself over the coals for first cheating on and then leaving Hadley, the muse who embodied his aesthetics of unpretentious clarity and rigor. The resulting memoir, A Moveable Feast, wasn’t published until 1964, three years after Hemingway committed suicide.

In many ways, the posthumously published nonfiction work provided a tonic for the shock of the shotgun blast that ended his life while cementing his myth. If The Sun Also Rises is a Bible for a certain kind of bohemian American who dreams of finding him- or herself in a foreign capital, A Moveable Feast is that rare book by an outsider that nationals embrace as their own. When terrorists killed 130 innocent people on November 13, 2015, in a series of attacks throughout Paris, copies of Hemingway’s hymn to the city sold out almost immediately. The book became a fixture of the memorials to victims that sprung up at the sites of the bloodbaths, as crucial to the mourning as flowers and hand-scrawled notes of love and endurance. It was the rare moment in this day and age when literature is called out of the classroom to console and heal the general public. The book’s role in this recovery is encapsulated by its French title, which served as a rallying cry for not giving in to fear and hatred: Paris est une fête, or Paris is a celebration.

Paris bookends Hemingway’s career in a way that few other celebrated literary cities can claim to define a great writer. But between those two significant periods, other interesting chapters of his life also took place in Paris. The following story, “A Room on the Garden Side,” published here, in The Strand Magazine for the first time, records one of them.

On August 25, 1944, Hemingway rode into Paris as part of the liberating force that toppled the Vichy regime and sent the occupying Nazis into retreat. Technically, Hemingway was a reporter, but in the thick of action he played the role of soldier and took up arms. As the late biographer Michael Reynolds noted, World War II found him “working under contradictory compulsions: as a correspondent he was supposed to be a noncombatant gathering printable war news; as unofficial liaison officer with the French Resistance while working with the OSS [the proto-CIA Office of Strategic Services], he was an irregular combatant who must never write of his activities.” Alongside OSS colonel David Bruce, Hemingway trailed General Philippe Leclerc’s 2nd French Armored Division into Paris before leading their raggedy crew of irregulars to the famous Ritz Hotel, the writer’s favorite home away from home. Combat historian S. L. A. Marshall later wrote of a victorious dinner a small band of American officers shared with the writer at the hotel. “We think we took Paris,” they captioned a menu card that the party of nine jointly signed as a souvenir. “But we agreed on something else. Hemingway said it: ‘None of us will ever write a line about these last twenty-four hours in delirium. Whoever tries it is a chump.’ On that pledge, we solemnly shook hands, raised our glasses, broke up, and redeployed.”

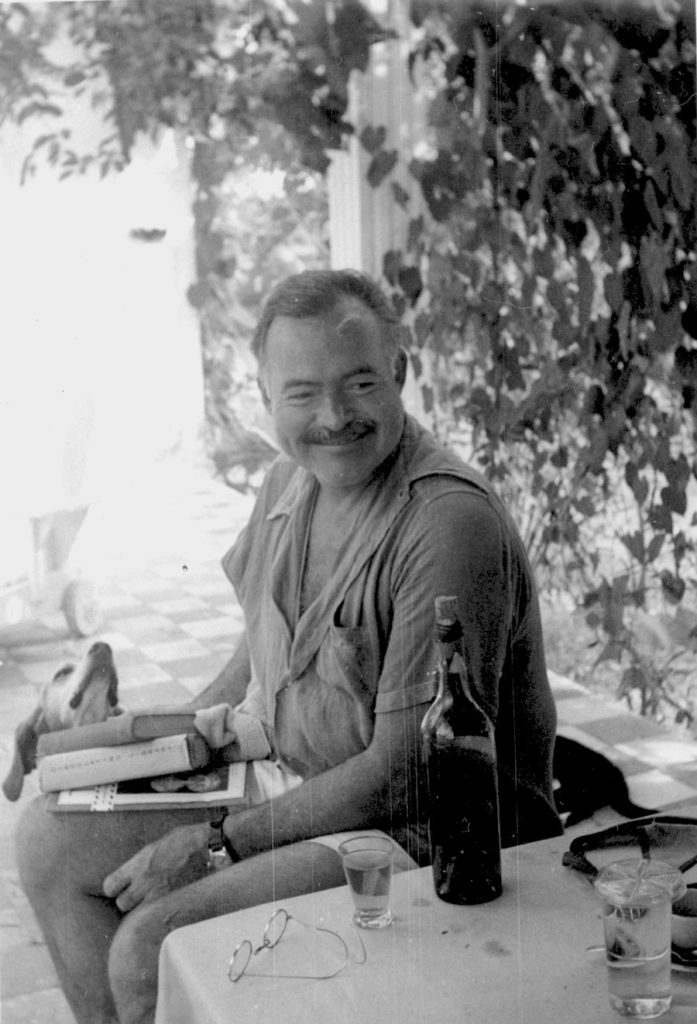

Ernest Hemingway (From: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential library and Museum, Boston)

Yet Hemingway did write about the liberation of Paris. In two predictably Papa-centric dispatches for Collier’s the next month he told a somewhat melodramatic version of events, though he left out the Ritz Hotel. An account of his stay that historic night wouldn’t emerge for another decade as Hemingway began the long process of reminiscence that led to A Moveable Feast. “A Room on the Garden Side” is one of a quintet of short stories about World War II completed in 1956, only one of which has previously appeared in print. Biographers and historians who visit the Ernest Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, Massachusetts, have had access to the story for decades, although they make only glancing reference to it.

Susan F. Beegel referenced the story in an excellent article that appeared in the now-defunct journal Studies in Short Fiction in the 1990s. According to Beegel—the godmother to many of us scholars who came of age during the years she edited The Hemingway Review from 1992 to 2014—the story contains all the trademark elements readers love in Hemingway. The war is central, of course, but so are the ethics of writing and the worry that literary fame corrupts an author’s commitment to truth. For readers who love a little controversy, the story even includes some gratuitous swipes at rival novelist André Malraux (“Colonel André”). The French hero had flown combat missions and spent time as a German P.O.W., but he also exuded an air of pomposity that miffed his American counterpart and made him ripe for parodying. Male camaraderie is another important theme, as is, typically, the importance of good food and wine to calibrating one’s senses. As in most of his fiction, Hemingway judges his characters by their willingness to accept moral accountability for their actions.

Mostly what “A Room on the Garden Side” captures, though, is the importance of Paris. Steeped in talk of Marcel Proust, Victor Hugo, and Alexandre Dumas, and featuring a long excerpt in French from Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, the story implicitly wonders whether the heritage of Parisian culture can recover from the dark taint of fascism. The question is deeply personal, with Hemingway’s alter-ego narrator, Robert, realizing he must not remain in the city if he is to preserve its meaning in his own memories. “The town would never look the same again unless you left it when you should,” he admits in the final line. Like the best Hemingway sentences, the implications are far more complex than the words themselves.

“A Room on the Garden Side” is published here for the first time thanks to generous permission from the Hemingway estate. As this issue of The Strand Magazine reaches newsstands, nearly 500 members of the Ernest Hemingway Society are gathering in Paris to celebrate the relationship between this place and this writer. It is our first official Hemingway Society conference in Paris in twenty-five years, and the largest ever in our thirty-eight-year history. Our membership isn’t composed only of professors and scholars. Nearly forty percent of us come from other professions—businessmen, collectors, booksellers, doctors, lawyers, everyday readers—bound only by our common affection for the twentieth-century’s most famous writer. Helping make this story available through our informal partnership with the estate and The Strand is our way of commemorating our own return to these intoxicating, inspiring arrondissements and quartiers. We arrive eager to write our own memories as we follow in Hemingway’s footsteps, and we take as our motto the title of one of A Moveable Feast’s most famous chapters: “There is Never Any End to Paris.”

Love all things Hemingway! His work is timeless! Always fresh and relevant…cutting edge!