The Adventure of the Hemingway Manuscripts

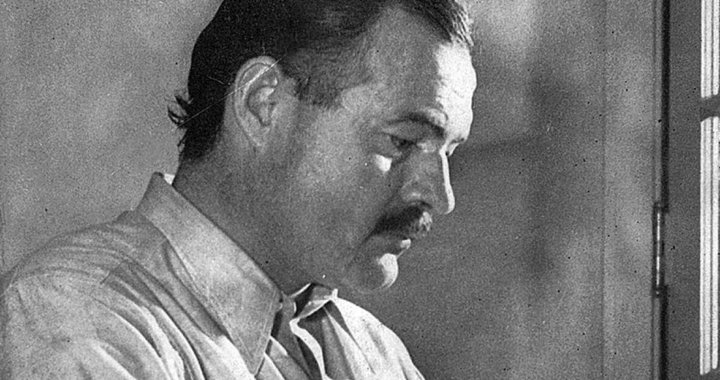

Congratulations to The Strand on being first to publish Ernest Hemingway’s World War II short story, “A Room on the Garden Side.” Having written a scholarly essay on this story twenty-five years ago, I’ve been asked to offer some personal reflections on how I “discovered the piece… back in the days before the Internet.” Everyone loves a good discovery story, preferably involving a flashlight and a cobweb-covered trunk in an old attic. But the truth is that I simply read about “Room’s” existence in a book and went to the Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library to see it. The really Strand-worthy adventure is the story of how Hemingway’s manuscripts got to the Kennedy Library in the first place.

When Ernest Hemingway committed suicide in Ketchum, Idaho on the morning of 2 July 1961, his grieving widow Mary was confronted with her first problem as his literary executor—and it was an emergency. The couple’s real home was in Cuba, the now-famous Finca Vigía estate in a tranquil village just outside Havana. They had walked out the door expecting to return, leaving behind all of their possessions—including filing cabinets stuffed full of story ideas, letters, and photographs at the Finca and an enormous stash of valuable manuscripts in a Havana bank vault. But the Cuban Revolution had intervened. Fidel Castro was seizing and nationalizing private property, and in the wake of the recent, disastrous, CIA-sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion, the U.S. and Cuba had severed diplomatic relations.

It was now illegal for Americans to travel to Cuba, but Mary was able to obtain permission through a friend in the Kennedy administration. Once there, she received a visit at the Finca from Fidel Castro himself. If she would donate the house and its contents to the people of Cuba, to be turned into a national museum, she would be allowed to depart with some personal possessions, including paintings by André Masson, Paul Klee, and Juan Gris that Hemingway had collected during the Paris years,1 and, most importantly, Hemingway’s papers. Mary agreed. The Cuban government had already confiscated the manuscripts in the Havana bank, but now they were returned to her—some thirty to forty pounds of paper, including the original typescript of The Old Man and the Sea, and the as-yet-unpublished manuscripts of Islands in the Stream, The Garden of Eden, and True at First Light. The cache may also have included “A Room on the Garden Side,” written in Cuba in 1956. Mary stored the manuscripts in a locked suitcase.

A new problem arose. To leave Cuba, she would have to fly on a Pan Am prop plane from Havana to Miami. The policy was strict—hand luggage only, no exceptions. Down on the docks, Mary accosted the captain of an American-flagged trawler that had come in for repairs. After considerable bargaining, she managed to persuade him to carry her “household goods” to Tampa, in exchange for a sum equal to the value of a hold full of shrimp. But in those chaotic days following the Revolution and the Bay of Pigs, no American vessel would be allowed to leave Cuba carrying valuable private property away. Mary appealed to Castro. “There’s a little law we’ll have to break,” he said.

One night not long after, a government aide arrived and told Mary to have her cargo on the dock early the next morning. And so a large cache of Hemingway’s priceless manuscripts, together with paintings worth a quarter-million dollars—all uninsured—headed out into the Gulf Stream aboard a shrimp boat, the last American vessel to clear the port of Havana. The voyage, with its air of international intrique, recalls To Have and Have Not, whose tough-guy hero, fisherman Harry Morgan, smuggles illegal immigrants, liquor, and bank-robbing revolutionaries between Havana and Key West. As for Mary, she left Havana for the last time aboard a Pan Am plane packed to the roof with fleeing Cuban families sitting on each other’s laps. In her purse? Jewels worth half-a-million dollars—in an envelope bound with a rubber band. Cuban friends had asked her to take them to relatives in Miami. She was gambling—correctly—that customs officials would not search the purse of a Nobel Prize winner’s widow.

Mary collected the Cuban papers from the Tampa warehouse, but her job of gathering Hemingway’s manuscripts was far from over. There were manuscripts with his publisher, Charles Scribner’s Sons; at the house in Idaho; in safe deposit boxes in New York and Miami; in a Louis Vuitton trunk in a hotel storeroom in Paris. But boxes stacked in a back room of Sloppy Joe’s Bar in Key West presented the biggest challenge. For more than a month, working six to seven hours a day, swathed in big white bartenders’ aprons to protect their clothes from dust and mold, Mary and an assistant retrieved documents from boxes containing not only family letters, drafts of early short stories, a manuscript of A Farewell to Arms, and hand-corrected proofs of Death in the Afternoon, but the skeletons of dead mice, rats, and cockroaches.

In the end, Mary assembled more than 19,500 pages of manuscripts, many of them crumbling and held together with rusted pins and paper clips. The papers included the canonical works in every stage from first draft to final proof, along with their outtakes—the original opening of The Sun Also Rises that F. Scott Fitzgerald urged Hemingway to cut, for instance, and dozens of alternate endings for A Farewell to Arms. Present too were 3,000 pages of unpublished works—novels, memoir, travelogue, and short stories. Distinguished literary critics and college professors began lining up to explain to Mary how this trove should be managed, and how willing they would be, for literature’s sake, of course, to take this onerous task from her inexperienced hands. Nevertheless, Mary, who had been a war correspondent for Time-Life before marrying Hemingway, persisted in believing she could handle her husband’s legacy by herself, thank you very much.

She invited English professor Philip Young and archivist Charles Mann, both from Penn State University, to prepare an inventory of the manuscripts for her. It was painstaking labor, a bit like assembling a 19,500-piece jigsaw puzzle, to figure out which fragments of published and unpublished works went together, reunite them, describe them, organize and catalogue them. In 1969, Mary gave Young and Mann permission to publish the results of their efforts—The Hemingway Manuscripts: An Inventory—and yes, this is where I “discovered” “A Room on the Garden Side.” It’s still the best place to search for unpublished Hemingway stories.

Now Mary was ready to choose a library to become the permanent repository of Ernest Hemingway’s papers. The Library of Congress was interested. The New York Public Library. But Mary connected with another widow at work on preserving a famous husband’s legacy—Jacqueline Kennedy. The two women had met at a 1962 White House banquet for American Nobel Prize winners. Always a devoted supporter of the arts, Mrs. Kennedy wanted to make the papers of this outstanding twentieth-century American writer, one of her husband’s favorites, part of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library being created in Boston. There they would be cared for in perpetuity and made accessible to the people of the United States by the crack library professionals of the National Archives and Records Administration.

All this is why we can “discover” unpublished short stories such as “A Room on the Garden Side”—and many other treasures besides—in the Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library instead of in brass-bound trunks, old clocks, and hidden staircases.

1 Fortunately, the most valuable painting owned by the Hemingways, Joan Miró’s “The Farm,” was out of the country, on loan to the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Sources: Mary Welsh Hemingway, How It Was (Alfred Knopf, 1976); Valerie Hemingway, Running with the Bulls: My Years with the Hemingways (Ballantine, 2004); Philip Young and Charles W. Mann, The Hemingway Manuscripts: An Inventory (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1969).