by Charles L.P. Silet

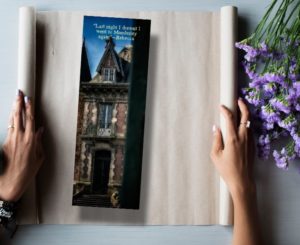

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” The opening line to Daphne du Maurier’s most famous novel, Rebecca is one of the great opening lines in English fiction. In one stroke, du Maurier establishes the voice, the locale, and the dream-like atmosphere of the story. It’s not surprising that Alfred Hitchcock used the same opening line for his celebrated cinematic adaptation of the novel—one which many critics feel is among his most accomplished. Although Daphne du Maurier was one of the most popular authors of her day and wrote or edited dozens of books—biographies, plays, and collections of letters as well as works of fiction— she is best remembered today for only a handful of novels including, of course, Rebecca.

Daphne du Maurier was born on May 13, 1907 in London to Muriel Beaumont, an actress, and Gerald du Maurier, an actor and theatrical manager. Gerald’s father, George, was a famous illustrator, especially known for his work in the British humor magazine Punch. He was also the author of three best-selling novels: Peter Ibbetson, Trilby (with its famous character Svengali), and The Martins. The du Mauriers were well-established in the artistic world, so Daphne—the middle child of three girls—grew up in a privileged and slightly bohemian environment, one in which she met the famous of the London stage as well as the popular writers of the day.

Daphne received the usual haphazard education of young women of her class and time. However, she read voraciously, especially in the standard British classics. After finishing at a school near Paris, she moved into the family home, Ferryside, in the harbor town of Fowey on the Cornish coast. Later she rented a local estate, Menabilly, located nearby, which became one of the models for Manderley. For most of her adult life she resided primarily in the area around Fowey (except when she left to travel with her husband, F.A.M. (Boy) Browning, who was a professional soldier) and set a number of her novels, including Rebecca, in that area.

Du Maurier was blessed with an active imagination and made up stories to act out with her two sisters as they were growing up. Often based on the fiction she was reading, these stories of adventure and romance set the tone for her later best-selling fiction. She began writing short stories in the late 1920s. Her first publication, “And Now to God the Father,” appeared in the May 8th issue of The Bystander, edited by her uncle Willie Beaumont, her mother’s brother. As she later would write in her autobiography, Myself When Young (1977), “I went self-consciously into the W.H. Smith’s [the booksellers] in Fowey and bought a copy, hoping the girl behind the counter did not know why I was getting it.” Du Maurier’s self-effacing reaction to her first publication was characteristic of her response to her later fame as well. She remained leery of self-promotion and publicity throughout her professional life.

Although she sold a number of other short stories to The Bystander, she quickly realized that if she was going to reach financial independence as a writer, she would have to turn her hand to longer works. During the autumn of 1929 she began her first novel, The Loving Spirit, which became the first of her many books inspired by her life in Cornwall. In The Loving Spirit, du Maurier first put to use the combination of romance, adventure, history, and a sense of atmosphere that would characterize all of her later fiction. It was a winning combination. Over the next fifty years she turned out a couple of dozen books, half of which—and the most memorable—were set in Cornwall. One of the most famous, Jamaica Inn, was suggested in part by a stay in the old coaching inn, long associated in local history with the Cornwall smuggling trade.

Although her first novels, The Loving Spirit (1931), I’ll Never Be Young Again (1932), The Progress of Julius (1933), and Jamaica Inn (1936), sold well and established her as an author in Great Britain, it was the publication of Rebecca in 1938 that brought Daphne du Maurier international recognition. The story of Rebecca is probably as well-known today for Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 film (with Laurence Olivier as Max de Winter and Joan Fontaine as the second Mrs. de Winter) as it is for du Maurier’s novel. With an outstanding supporting cast (consisting of Judith Anderson, George Sanders, Nigel Bruce, Reginald Denny, C. Aubrey Smith, Leo G. Carroll, and du Maurier’s old family friend Gladys Cooper) the film remains a true classic. However, the popularity of Hitchcock’s film was originally built on the fame of the best-selling novel, which remains in print some sixty years after its publication. Hitchcock and du Maurier proved a durable film/fiction combination. While still working in Great Britain, Hitchcock filmed a version of Jamaica Inn (1939) with Charles Laughton and Maureen O’Hara and his 1963 film, The Birds, was also based on a du Maurier short story.

The novel Rebecca is a curious hybrid—a mixture of romance, murder mystery, and the gothic. The romance, of course, was brought to life by Hitchcock and Hollywood through Joan Fontaine and Laurence Olivier, but it is at the core of the novel as well. A naive young woman—interestingly never named in either the novel or the film—is alone in the world (a paid companion to an older, coarser, social-climbing woman) until she meets the handsome, wealthy, and recently widowed Maxim de Winter. He had been married, we are told early on, to the accomplished, beautiful Rebecca who tragically died in a boating accident off the south coast of Cornwall near the de Winter family estate of Manderley. An older, distraught wealthy man meets a younger, callow impoverished woman whom he decides to marry in order to restore his mental health—the plot is common to any number of traditional English romantic novels, most obviously Jane Eyre.

The mystery evolves slowly and involves the death of Rebecca around which du Maurier deftly creates a plot twist. Up to the time of the accidental discovery of Rebecca’s body, both the reader and the heroine have been led to believe that Maxim still loves his first wife. However, at this point in the novel Maxim reveals that he had never loved Rebecca, that in fact he had despised her, eventually developing toward her a loathing so powerful that it had led him to kill her. In the film version, Rebecca’s death is portrayed as accidental.

The gothic elements revolve around the house itself—Manderley—and its menacing housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, one of the eeriest figures in fiction who, in her own particular way, terrorizes her new mistress. Although du Maurier forgoes the usual trappings of gothic writing—hidden staircases, floating ghosts, and the like—the atmosphere of the house is so pervaded by the memory of Rebecca that the marriage of the romantic couple is nearly destroyed and the young bride, believing her marriage a failure, nearly commits suicide—with the encouragement of Mrs. Danvers. It is Mrs. Danvers who destroys Manderley in the end by setting it on fire before disappearing from the novel. In the Hollywood version, she is destroyed along with the house which she has set ablaze.

Despite the fact that the film is fairly true to du Maurier’s original, there are other significant differences which affect the tone as well, such as those between the respective closing scenes. At the film’s conclusion, Maxim and his wife meet during the burning of Manderley and embrace in front of the flames of the house, a typical Hollywood happy ending. In the novel, however, after the destruction of Manderley, Maxim and his wife are described as living in self-imposed exile somewhere on the European continent. There they lead a quiet, placid life, skirting carefully around subjects that might rekindle memories of Rebecca and Manderley and “that sense of fear, of furtive unrest.” The ending of the book, therefore, is much darker than that of the film. By the end of the novel, the dream-like opening has taken on a more nightmarish quality, one that more accurately reflects the way the past still haunts the lives of Maxim and his second wife.

Du Maurier’s fiction was a durable source for Hollywood movies. Besides those made by Hitchcock, My Cousin Rachel (1952), directed by Henry Koster and starring Olivia de Havilland and a young Richard Burton in his American debut, proved a successful adaptation of du Maurier’s novel of the same name. In 1959, The Scapegoat was made into a film with Alec Guiness and Bette Davis. Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973), with Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, also effectively captured her occult short story on film. With their strong psychological plots and emphasis on atmosphere, du Maurier’s novels and stories lent themselves easily to film and through the years the films based on her fiction increased the popularity of her work and enlarged her fame.

Daphne du Maurier continued actively writing for almost forty years after she wrote Rebecca, and indeed most of her work appeared after the war. In 1969 she was made a Dame Commander, Order of the British Empire, and in the same year she finally left her beloved Menabilly. In 1977 she was awarded the Grand Master Award by the Mystery Writers of America, and in 1982 she published her last books, The Rendezvous and Other Stories and, appropriately enough, The Rebecca Notebook and Other Memories. She died in1989 in Cornwall at the age of 82. Throughout her life the fame of Rebecca, both in print and in film, provided her with a constant bond to the past

The End

I have never ever read a book like Rebecca, which I have read and reread as many times I cannot even remember to count. Whenever I search my book collection for something to read it is without failure Rebecca I chance to reread once more. The mystery, the passion, the longing and just the storyline does something to my mind and intellect which I am not able to put in words.

The author, has an air of mystery and emotion that almost makes me feel as if I am her re-incarnated. I look at her face when young and when old and cannot but have an uncanny feeling of “This me!” Words fail me to say anything more.