To subscribe, please visit our subscriptions page. For back issues, mystery books, and much more, visit our shop.

In this article from issue 4, Mike Ashley looks at the life of Vidocq, a thief turned turned detective who was to prove the inspiration for many great fictional detectives.

If you were to go by either Edgar Allan Poe or Arthur Conan Doyle you might think that François Eugène Vidocq, the world’s first real life private detective, was an irrelevance. “Vidocq,” Poe wrote in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “was a good guesser, and a persevering man. But, without educated thought, he erred continually by the very intensity of his investigations.” Through the voice of Sherlock Holmes in A Study in Scarlet, Conan Doyle states of Lecoq (a fictional detective created by Emile Gaboriau-based largely on Vidocq), “Lecoq was a miserable bungler. He had only one thing to recommend him, and that was his energy.” Yet, despite their disparaging remarks about him, both writers drew on Vidocq’s character and activities in developing their own detectives. Vidocq, like Holmes, was a master of disguise and used the network of the underworld to seek out his clues. As for Poe, Julian Symons went so far as to say, “He had read Vidocq, and it is right to say that if the Mémoires had never been published Poe would never have created his amateur detective [C. Auguste Dupin].”

It is not only detective fiction that owes much to the work of François Eugène Vidocq, but the world of professional investigation as well. He was instrumental in establishing the first detective bureau in the world, the Brigade de la Sûreté, in 1812, and opened the world’s first private detective agency, Le Bureau des Renseignements, in 1834. The success of these agencies encouraged Britain’s Scotland Yard to create the Criminal Investigation Department in 1842. It was not until 1850 that Alan Pinkerton set up his private detective agency in Chicago.

By 1841, when Poe referred to him in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Vidocq’s name was well known throughout the English-speaking world. If he lacked anything it was certainly not his gift for self-promotion. He was almost a national hero in France, where it was almost entirely due to his efforts that the crime rate was reduced by 40% between 1812 and 1820. Furthermore it is impossible to assess the total number of crimes that he solved.

Needless to say the French police hated him. To him went all the glory-to them all the blame. For almost the entirety of Vidocq’s career the police attempted to ruin him. In return he promoted himself to greater glory.

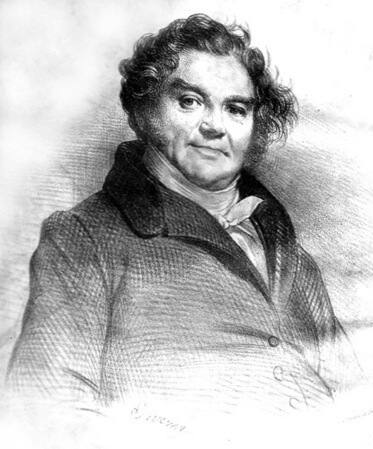

In looking back over Vidocq’s life what is the truth? His own romanticized version of his life, or the police’s vilifications? In fact, Vidocq’s life rapidly became blurred with his legend, so it is fair to say that he was both the world’s first practicing private detective and the world’s first fictional one! His life and books had an immense influence on the more sensational literature of the nineteenth century. So who was he?

In his accounts of his exploits and in the plays based upon them, Vidocq loved to suddenly unmask himself at the end and reveal to all assembled, “I am Vidocq!” So, let us remove the disguise, layer by layer, to find the man beneath.

François Eugène Vidocq was born in Arras in Northern France on 24 July 1775, the son of a very popular local baker. Although he was a good scholar, his interests lay elsewhere and by his teens he had become a dashing swordsman with a yen for travel, as well as the local Don Juan-Vidocq and young women were seldom apart for the rest of his life. He was a keen observer of people (an invaluable skill in the detective business), hence his ability to disguise himself and his ability to read body language (long before it was a science) in order to identify criminals.

With the onset of the French revolutionary wars it was inevitable that Vidocq would be conscripted. He fought with distinction, rising to the rank of senior lieutenant. Unfortunately it was at this time that his delight in disguise landed him in trouble. In 1795, after a period at home on sick leave, instead of rejoining his regiment he disguised himself as a captain and became involved with card sharks in Brussels. He was arrested, and-fearing that his real identity would be uncovered-escaped, becoming both a deserter and a fugitive from the police. Although Vidocq found it easy to change identities, he did not find it easy to maintain a low profile. He had a very public argument with a captain of engineers over a woman and was arrested for breach of the peace.

While in prison he helped a peasant-who had been imprisoned for six years for stealing grain for his starving family-by forging a formal pardon for the man’s release. It was later discovered that the pardon was a forgery. Vidocq knew that if he was found out the sentence would be serious so again he escaped. For the next ten years he was frequently captured but just as frequently escaped. At one point, in 1798, he was held long enough to be brought to trial for the forgery, and was sentenced to eight years in what was known as “the galleys” at Brest. This was a maximum-security prison where the inmates wore leg and arm chains at all times. Amazingly he escaped, disguised as a sailor, and spent the better part of a year serving on a privateer before being recognised the following summer and returned to the galleys with double the sentence. Yet again he escaped, this time marching out of the town as part of a funeral procession.

Vidocq now had considerable status amongst the criminal underworld as one who had escaped not once, but twice, from the galleys. Yet he was not a criminal by nature. He was more a victim of his own good nature and, at times, hot-headedness. When he refused to join a gang of robbers in Lyons they betrayed him to the police. Arrested again, Vidocq faced a bleak future. Fortunately the president of the Lyons police, Jean-Pierre Dubois, was aware of Vidocq’s abilities and felt they could be put to good use. Dubois gave Vidocq the choice of either going back to the galleys for what would probably be the rest of his natural life or becoming a police informer. Vidocq had little choice. He was ideal as an informer, because the criminal underworld accepted him as one of their own. However, the occasion arose where Vidocq’s testimony was required in open court and his identity was revealed. Dubois gave Vidocq new papers and provided him with a new identity, under which he left Lyons for Paris.

Over the next few years Vidocq’s life was itinerant as he drifted from town to town, moving on whenever he was recognized. Eventually, after being blackmailed by some robbers, he decided to chance his arm again. In 1809 he went to the criminal division of the Parisian Police offering information on the gang provided he was granted immunity. According to one colorful tale, Vidocq helped recover the Empress Josephine’s stolen emerald necklace, thereby raising his profile with Napoleon. Whatever the truth, Vidocq was employed by the Parisian Police, not simply as an informer but as a full-fledged spy.

Over the next few years Vidocq’s life was itinerant as he drifted from town to town, moving on whenever he was recognized. Eventually, after being blackmailed by some robbers, he decided to chance his arm again. In 1809 he went to the criminal division of the Parisian Police offering information on the gang provided he was granted immunity. According to one colorful tale, Vidocq helped recover the Empress Josephine’s stolen emerald necklace, thereby raising his profile with Napoleon. Whatever the truth, Vidocq was employed by the Parisian Police, not simply as an informer but as a full-fledged spy.

Now Vidocq’s energy and inventiveness began to shape his destiny. He adopted different personalities to blend into the underworld. He began to apply deductive principles to his investigations. At one burglary he noticed a bootprint in the garden and arranged for a plaster cast to be made. Via his underworld network he already had a clear idea of the burglar’s identity, but when he was able to match the plaster cast to the man’s boots the case was sealed. Vidocq also started to keep files on all known criminals, noting their preferred methods as well as their betraying details. He even established a set of rules for the investigation of a crime and what to do in the event that a cover is blown. He was, in fact, starting to employ scientific methods and reasoning in his investigations-establishing the science of criminology.

Vidocq had long argued that crimes were best investigated by officers in plain clothes, not uniform, and that a special division of the police should be established. He at last got his way in October 1812. Napoleon had denuded Paris of young men for his advance on Russia and the police found their resources stretched. The crime rate soared. Yet again, Vidocq petitioned the Ministry of Police to establish a plain-clothes bureau, and this time it worked. He was allowed to employ eight men (all of whom turned out to be former criminals) and establish a formal office. The Brigade de la Sûreté, was created.

Thereafter Vidocq went from strength to strength. Napoleon gave the Sûreté, his blessing the following year and it became La Sûreté Nationale. Vidocq opened branches in Arras, Brest, Lyons, and Toulouse, establishing a significant network of informants. During these early years the claims of Poe and Doyle may have been justified. Vidocq did not operate with much finesse. He hardly needed to. His underworld contacts were usually only too ready to inform. The police were convinced that Vidocq was taking bribes and sometimes creating and “solving” his own crimes merely to seem all the more impressive. But, for all that the police despised Vidocq, they could never prove anything against him. Instead his stature rose with the authorities and, in 1817, he was even able to obtain a provisional pardon of the long outstanding forgery charge.

By the 1820’s Vidocq was employing many more scientific skills. In 1822 he was one of the first investigators to have a bullet retrieved from a body in order to compare it with those in a suspect pistol. In 1825 he used bloodstains to trap a murderer and by 1826 he was exploring the use of fingerprints-though he never could find a suitable ink. He did invent his own indelible ink as well as a special form of paper which was difficult to forge-this same paper was later the basis for French bank notes. Vidocq acquired a sizable income from selling his special paper and ink as well as from other legal but borderline activities, such as taking money from army conscripts and sending others in their place. The police were constantly trying to trap him and, in the end, Vidocq became tired of the endless confrontations. On 20 June 1827, he resigned after the new Prefect of Police made it clear that he had no time for him. Vidocq had plenty to keep him busy, amongst other things settling down to write his Mémoires, which were to immortalize his name.

The police soon found they could not operate without him and during the revolution of 1830 Vidocq was reinstated, this time as Deputy Prefect. However, he resigned again in November 1833, unable to work within the police hierarchy and on 3 January 1834 he set up his own private detective agency, Le Bureau des Renseignements-the first in the world.

This infuriated the police even more. Although what Vidocq had done was not illegal-provided he did not masquerade as a policeman-the police were convinced that he was exploiting them. Eventually, in 1842, probably as a result of a police set-up, Vidocq was arrested for posing as a policeman. Although the trial made it clear he had done no such thing, he was nevertheless found guilty and was only released on appeal, after spending ten months in prison.

Visit our shop for a selection of the best in mystery books, gifts, and more.

Vidocq was now nearly seventy, and his incarceration in one of the worst prisons in Paris (the Conciergerie) had not improved his health. However, he continued to operate his Bureau, and the police continued to use his services. By now they realized that they could never better him and that, considering his age and health, he would soon cease to be a problem. His fame had, of course, spread. In 1843, Scotland Yard sought his advice on the newly established Criminal Investigation Department, and he visited London in 1845. He eventually retired in 1849, but even then ensured that he would have the last laugh. He pleaded poverty, dressed as a beggar, and implored for an increased police pension, which he was granted. Vidocq was anything but poor-he had amassed a fair fortune during his lifetime, much of which he had invested in paintings, business, and property. He was so convincing, however, that it was generally believed that he died in poverty.

On the day he died, 1 May 1857, the police confiscated all his files. He was buried at the Church of Saint-Denis in Paris. Throughout his career Vidocq had been close friends with the major writers of the day-Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Theophile Gautier, Eugène Sue, Honoré de Balzac. All of these writers drew upon Vidocq’s experiences for their fiction.

In his novel, Le Père Goriot (1834-5), Balzac introduces the dubious character of Vautrin, one of the many disguises of arch-criminal Jacques Collin. Vautrin is arrested before he can encourage the main character, Rastignac, to become involved in a murder plot. But that’s not the last we see of Vautrin. He reappears in other novels by Balzac-all part of the author’s vast Comédie Humaine tapestry-and eventually forsakes crime. By Le Député d’Arcis (1847) he has become a minister responsible for police and public health in an Italian principality. Throughout the various books, Vautrin’s machinations mirror many of the episodes Vidocq loved to boast about.

The characters of Rodolphe in Eugène Sue’s Les Mystéres de Paris (1843) and Jean Valjean in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables (1862) also share many of Vidocq’s attributes. Sue’s Les Mystéres de Paris (Mysteries of Paris) was so popular that in 1844 Vidocq produced his own Les Vraie Mystéres de Paris (The True Mysteries of Paris). Vidocq may not have personally written the book-it is known that his author friends often worked alongside him when he was writing. Of special significance is Les Voleurs (1836),which was probably drafted by Vidocq and polished by Alfred Lucas, a former police officer who had worked at Vidocq’s agency. The book is a series of stories about individual master criminals who are eventually beaten by a master detective. What is important about Les Voleurs (or The Thieves), apart from its being one of the first books about a detective, is that, in it, Vidocq considers criminals to be victims of a society that has ceased to care about the poor or the unfortunate.

It is hardly surprising, given Vidocq’s prominence in the field, that Poe chose Paris as the setting for “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (Graham’s Magazine, April 1841). Although the character of Dupin is not based specifically on Vidocq, he was very clearly developed from the world that Vidocq had created. But it was in France that the detective novel proper began to emerge, still hanging onto Vidocq’s coat-tails. Fascinated by the work of both Poe and Vidocq, Emile Gaboriau brought those threads together with the publication of L’Affaire Lerouge (or The Widow Lerouge) in 1866. It introduced a private detective called Tabaret (based on Dupin) who uses deduction to solve the mystery of a corpse found in a cottage. Tabaret works alongside a police official, Lecoq, who is clearly fashioned after Vidocq. Not only are their names similar, but Lecoq is also a reformed criminal who enters the police force. By Gaboriau’s next novel, Le Crime d’Orcival (1867), Lecoq is an established police detective using the ratiocinative principles employed by Tabaret. Lecoq remains the hero of all the later novels. Les Esclaves de Paris (1868)-also known as Caught in the Net or The Champdoce Mystery-shows further Vidocqian connections as it pits Lecoq against the master criminal Mascarot (shades of Moriarty).

The underworld described by Vidocq and elaborated upon by Balzac, Hugo, and Sue heavily influenced Victorian English literature. You can see elements of it time and again in the work of Bulwer-Lytton, Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Thomas Hardy, and many more. The shade of Vidocq continued to haunt crime fiction for decades. In essence he was the forerunner of the villain-turned-hero supporter of the underdog who uses nefarious and borderline-legal means to solve crimes that baffle the police. You can see traces of him in LeBlanc’s Arsène Lupin, Hornung’s Raffles, Charteris’ Simon Templar, and even such pulp heroes as Lamont Cranston (The Shadow).

As with so many originals, Vidocq’s life has become so overshadowed and masked, not only by those he inspired, but by his own legend as well, that today, if he is mentioned at all, it is to dismiss his achievements as fiction. But he was real, and he was a true living legend.