WASHINGTON’S TOP TEN SPY SITES…Plus ONE

Espionage’s most sensitive secrets are often hidden in plain sight. A white chalk mark on a mailbox, a construction worker’s discarded dirty glove, an unattended garbage bag, even a dead rat will go unnoticed and untouched by passersby absorbed in their daily routine. However, for the spy, each of these could be a signal, a concealment for codes and cash or instructions for a new operation. When it comes to espionage, carefully calculated appearances of normalcy are the best cover.

Spies in Washington meticulously planned operations that blended seamlessly with the city’s parks, casual dining chains, and suburban landscape. Contrary to Hollywood fictions, spy wars are best fought silently—frequently visible to everyone but recognized by few.

The authors of best-selling Spy Sites of Washington D.C. (Georgetown University Press, 2017) reveal their picks of the Capital City’s ten (plus one) most significant sites of espionage history.

- Foxstone Park, 1910 Creek Crossing Road, Vienna, Virginia. FBI Agent Robert Hanssen, acknowledged as one of the most damaging spies to the U.S., signaled his Russian handler by placing a piece of white tape on the entrance sign to Foxstone Park. The tape confirmed that Hanssen had placed a package of secrets in a dead drop, code named ELLIS, located under a footbridge inside the park.

- Edward J. Kelly Park, Virginia Avenue at 21st Street NW, DC. Russian technical spy Stanislav Borisovich Gusev parked his car, then loitered in plain sight in the Edward J. Kelly Park across from the U.S. State Department. Sitting on a bench, he appeared to fidget inside his briefcase and then periodically feed the parking meter. All the while, Gusev was covertly recording transmissions from a bug concealed in a chair rail of a State Department conference room used by senior U.S. diplomats.

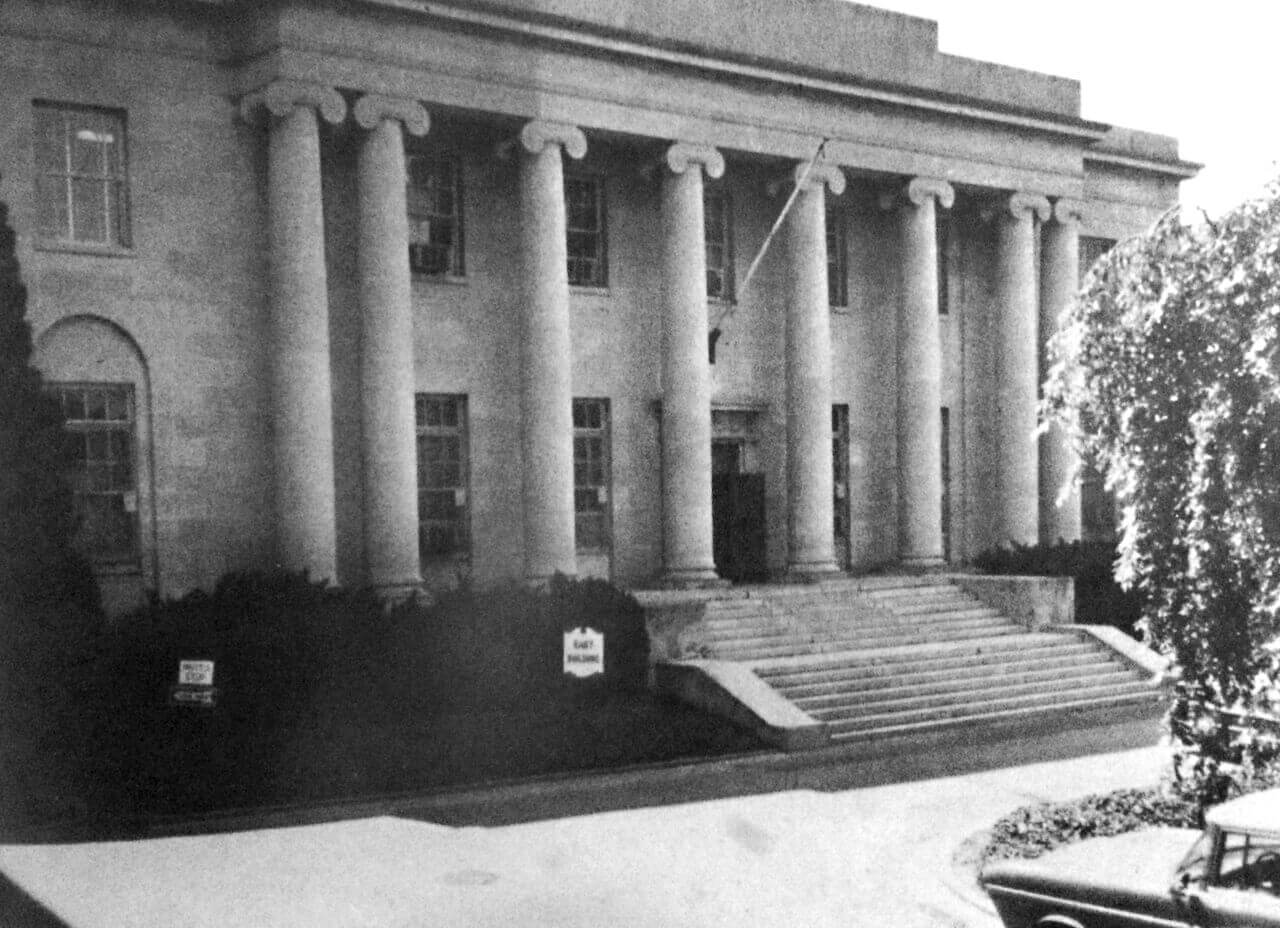

- OSS and CIA Headquarters, 2430 E Street NW, DC. Headquarters for the World War II intelligence organization Office of Strategic Services and subsequently for the Central Intelligence Agency, the site is now recognized among the National Register of Historic Places. After the CIA moved its headquarters to Langley, Virginia, buildings in the fenced compound housed the Office of Technical Service where spy gear that surpassed James

OSS Headquarters

Bond’s gadgeteer Q were designed.

- Pedestrian Bridge, Massachusetts Avenue at Little Falls Parkway, Bethesda, Maryland. Betrayal by traitorous CIA officer Aldrich Ames brought death sentences to several U.S. spies in the Soviet Union. Ames delivered secrets for cash to his Soviet handlers through a series of dead drops located throughout the Washington area. One was under the pedestrian bridge near Massachusetts Avenue and Little Falls Parkway, Bethesda, Maryland. Another was along a bridle path near a drainpipe in Wheaton Regional Park, Wheaton, Maryland.

- Pullman House, 1125 16th Street NW, DC. One of Washington’s grand mansions, built for the daughter of railroad tycoon George Pullman, the home was later bought by pre-Soviet Russia. It then became the Soviet embassy with the cramped fourth floor accommodating up to thirty Soviet intelligence officers in 800 square feet. Infamous spies such as Aldrich Ames, Ronald Pelton, and John Walker volunteered their “services” to the KGB by “walking in” at the stately mansion. Today the Pullman House is the Russian ambassador’s residence.

- Mayflower Hotel, 1127 Connecticut Avenue NW, DC. Celebrities and dignitaries feted at Washington’s Mayflower Hotel overshadow the many spies who worked, dined, and slept there. Early in World War II, George Dasch, a would-be Nazi saboteur, stayed in room 351. During the 1960s, CIA officers used the hotel’s lobby as the venue to perfect a new tradecraft technique, known as the “brush pass,” to pass information quickly and unnoticed between two persons in public. More recently, Stewart Nozette gobbled room service in a suite as he offered to sell secrets to an FBI agent posing as foreign intelligence officer.

- Hotel George, 15 E Street NW, DC. In one of the never-solved cases in espionage history, in 1941, Walter Krivitsky was found dead in his room at the Bellevue Hotel (today Hotel George). A defector from Stalin’s Soviet Union, Krivitsky died from a single gunshot to the head. Officially ruled a suicide, few believed the explanation. “If they ever try to prove that I took my own life, don’t believe it,” Krivitsky had told The New York Times. His death remains one of the mysteries of espionage history.

- Cameroon Embassy (Christian Hauge House), 2349 Massachusetts Avenue NW, DC. A colorful Cold War operation unfolded as FBI counterintelligence agents disguised as trash collectors drove a garbage truck into the courtyard of the Czechoslovakian e

Robert Hanssen’s Dead Drop Site

mbassy. Once inside the compound, a cooperating Czech handed them a cipher machine through an open window and the garbage men drove back out through the gates.

- Art Barn, Rock Creek Park, 2401 Tilden Street NW, DC. The Art Barn in Washington’s largest park was a rustic meeting place for amateur artists during the 1960s and 1970s. Unknown to those taking classes and attending exhibitions, the quaint structure was also a U.S. government listening post. Equipment secreted behind a false wall collected signals from nearby Soviet bloc compounds.

-

McDonald’s Parking Lot, 4200 Wisconsin Avenue NW, DC. Representing a youthful generation of Russian spy, the SVR’s Mikhail Semenko used the newest technology of tradecraft. From a seat inside a Ruby Tuesday restaurant (now closed), he transmitted covert messages wirelessly from his laptop to a Russian diplomat parked in the McDonald’s lot across the street. The ad hoc local area network would have been virtually undetectable had Semenko and others in his spy ring not been under surveillance. All were rolled up in 2010.

- International Spy Museum, 900 F Street NW, DC. Housed in what was once was an office building used by the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), the International Spy Museum opened in 2002 and is one of Washington’s “must-see” attractions. Displays feature enough spy gear to satisfy the most diehard James Bond fan along with the front door of the CPUSA offices.

Spy Sites of Washington, D.C.,published by Georgetown University Press, is available on online and at the International Spy Museum in Washington.

I also like Hanssen’s dead drop at the W&OD (Washington & Old Dominion) trail head in Vienna, VA. Great reuse of old railroad trackbed!