Dr. Watson on Sherlock Holmes

A Californian writes as a Victorian physician in her new Sherlock Holmes Adventure – ART IN THE BLOOD.

Of the many challenges faced in writing as Dr. John Watson, perhaps the most intriguing was that of simulating a medical doctor.

We all know the character of Dr. John H. Watson, narrator of most of the Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. He’s an upright and brave former army doctor, sensible, observant (yes he does see, and observe, Mr. Holmes, particularly all your foibles) and impeccably loyal.

Watson is also a crack shot, a man of integrity and action, with a keen eye for the ladies. While he has a bit of a gambling problem, he’s smart, kind, and quite funny.

Stylistically, Watson writes concisely but with a flair for the theatrical which he tempers with typical English understatement. He’s rarely poetic or metaphoric (but exquisite when he indulges), and inclines rather to crisp dialogue, shorter sentences and more exclamation points than others of his era. (!)

Getting Watson’s voice right takes intuition, mimicry and study. But John Watson is also a medical doctor. And that is where some serious research comes in – if one wants to see Watson in action in his chosen profession.

Strangely, Watson “doctors” little in the canonical tales — odd, since Conan Doyle was a medical man himself. (There is medicine aplenty, however, in Round the Red Lamp, Conan Doyle’s delightful collection of medical short stories.)

But I wanted some doctoring in my story. ART IN THE BLOOD is set in 1888, when the duo are 34 and 35 years old. Holmes’ cocaine use is already an issue between them, and a small subtext of the story focuses on Watson’s growing recognition of his friend’s almost bipolar mentality, as well as the downside of Holmes’ useful ability to hyperfocus (in a way we might today label mildly Aspergian). Through Watson’s lens, this book subtly explores Sherlock Holmes’ artistic temperament.

But it’s early in their partnership and Watson is still gathering data about his friend.

As writers, we cannot help but bring ourselves to the page, even when writing in the style of another. My predilections are not, perhaps, common ones. For example, I have been a medical science buff all my life and to this day wonder about my “road not taken.” In junior high school, our biology class had us dissecting rats – two students per rat. (Imagine the “trigger warnings” that such an assignment would elicit today, not to mention budget issues; we’ve impoverished our students… but I digress.)

I was so taken by this assignment (and annoyed by my partner’s cluelessness) that I convinced my parents to buy me my very own preserved rodent from a medical supply company, which I then dissected in our backyard on the picnic table. (And won the science fair, but again…)

Writing as Watson, I wanted to roll up my sleeves and do some serious doctoring. But medicine was very different then, and took some on-the ground research. In London, of course, arguably the center of the scientific world at the time.

A major hit of arcane information came from a visit to the Old Operating Theatre Museum which has preserved a Victorian operating room and displays a wealth of old medical equipment with alarming notes on how it was used. Example below.

But the Wellcome Library in London turned out to be the real mother lode. I discovered this mecca for historical medicine researchers with all the glee of a Disney-phile first setting eyes on a Disney Emporium.

But no Auroras and Mickeys for me; I love old stethoscopes, brass and glass contraptions, weird drug legends and arcane medical theories. Call me weird, I’m used to it.

It all started innocently enough, sorting through the Wellcome’s online cataloguing system.

But what to look up, exactly?

Writing a mystery is a bit like solving a soduku in that one circles round and round the thing, filling in bits until it all clicks happily into place.

My initial circling included a list: the 1888 treatments for cocaine addiction, shock, hypothermia, blood loss, broken limbs, and morning sickness. Some of my answers came in small leather-bound little booklets, so yellowed and aging that they had to be tied with linen ribbons.

Some looked like they’d not been touched in over fifty years. Maybe more.

Nothing beats primary resources in research. Cracking them gently open, I discovered wonderful stuff. Cocaine was available everywhere and used for everything, even to calm babies. It was a frequent anesthetic and pain reliever, for things like eye surgeries, and for the most part was considered non-addictive and certainly not dangerous.

But Conan Doyle makes Watson very leery of Holmes’ cocaine use, warning of long-term effects. That sentiment was not shared by most of the medical establishment. Conan Doyle was ahead of his time in this as in much of the forensic detective work he wrote about.

Looking at blood loss yielded some narrative juice, pardon the metaphor. Transfusions rarely worked back then. Blood types were unknown and doctors, when attempting to transfuse blood into their dying patients often killed them instead. No amount of ingesting fluids helped, and if the patient was unconscious this was dangerous.

Transfusions of water, milk, animal blood — many things were tried with little success. But every now and then, human blood worked…and a person to person transfusion method was known at the time. And thanks to the Wellcome, here’s what it looked like.

But of course the donor was in danger as well, from his/her own blood loss, shock or even from infection. Germ theory was well proven at the time but, astonishingly not yet universally accepted. (Although Watson clearly adheres to it in canon.)

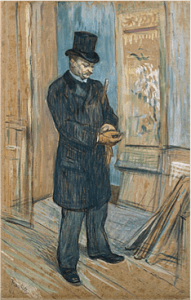

Another bit of doctor lore which came from a wildly different source tickled my fancy. The artist Toulouse Lautrec makes a brief appearance in ART IN THE BLOOD. Research detailed his love of all things English, which he spoke, but not as well as he thought, and his invention of the very real cocktail “the Earthquake” and his own struggles with addiction.

But it was the latter that yielded gold. Check out this “Portrait of Dr Henri Bourges‘ by Lautrec, painted three years after my story

In it, a dignified, well-dressed gentleman in a top hat stands at the entrance to Lautrec’s studio.  Dr. Bourges was a young physician who later went on to write a famous paper on diphtheria. And, he was also Lautrec’s best friend who lived with him for years. Bourges and Lautrec shared fun times but the doctor reportedly tried to keep his genius friend, who suffered from alcohol and drug addictions, from his own excesses.

Dr. Bourges was a young physician who later went on to write a famous paper on diphtheria. And, he was also Lautrec’s best friend who lived with him for years. Bourges and Lautrec shared fun times but the doctor reportedly tried to keep his genius friend, who suffered from alcohol and drug addictions, from his own excesses.

Does this sound like anyone we know?

A chance meeting between Dr. Bourges and John Watson was one of the moments I most enjoyed writing.

I have to say that I loved living in that gas-lit, dramatic yet cozy Victorian world, of sharing a dangerous adventure with my idol Sherlock Holmes, and perhaps best of all, being in the mind of that noble, funny, warm Dr. Watson…. including the chance to play out a role I gave up in real life, for a little bit of time, at least on the page.

PURCHASE Bonnie’s latest book from the Strand!