How I Look at Art

Navigating museums can be tricky. Blockbuster exhibitions have made what should be a quiet, intimate experience, too often crowded and difficult, chirping audio guides like crickets in the air, people jostling for a better view or worse, loudly critiquing the artwork to a friend. Sometimes I think art has become too popular and long for the days when I had the museums to myself. But I’m also glad art is popular, glad people want to see it and enjoy it as they should, since it is there for everyone.

So, what’s the answer? Well, if you can’t make your visit at an off hour, be strategic. Go online beforehand, check out the paintings you really want to see (though allow yourself to be surprised by a work that suddenly captivates you in person). And when you go, be patient, the crowd will eventually disperse, the guide will stop jabbering, people will move on. And then, when you have your moment alone with the artwork, stand your ground, you have earned it.

Here’s another idea: while everyone is crowding the blockbuster exhibit, go into the museum’s often ignored permanent collection, and amble through by yourself, or practically.

I tend to move quickly through exhibitions no matter what. Six years of art school and many more as a painter have trained my eye so I can spot what I want to look at. People often ask if they can go to a museum with me and I almost always say no. “I go very fast, and you will miss a lot. Go by yourself or with a quiet friend (you have plenty of time to discuss the work after).”

Art is not about words. It is about looking. About allowing yourself to connect with the artwork. Go close. Stand back. And most of all, be quiet, very difficult in our fast, noisy world. I think that’s why so many people don’t like museum-going and prefer experiences where it’s about spectacle and entertainment. I am not against art being entertaining. It is. But paintings and drawings are not nightclub acts or movies or light shows. They are what remains of a creative act, the artist applying paint to a canvas or moving charcoal or pencil across paper. What you are witnessing is the artist’s decision-making process, his or her hand, the way he or she has touched the canvas or paper and left a mark or a dab of color, and that experience is more than enough.

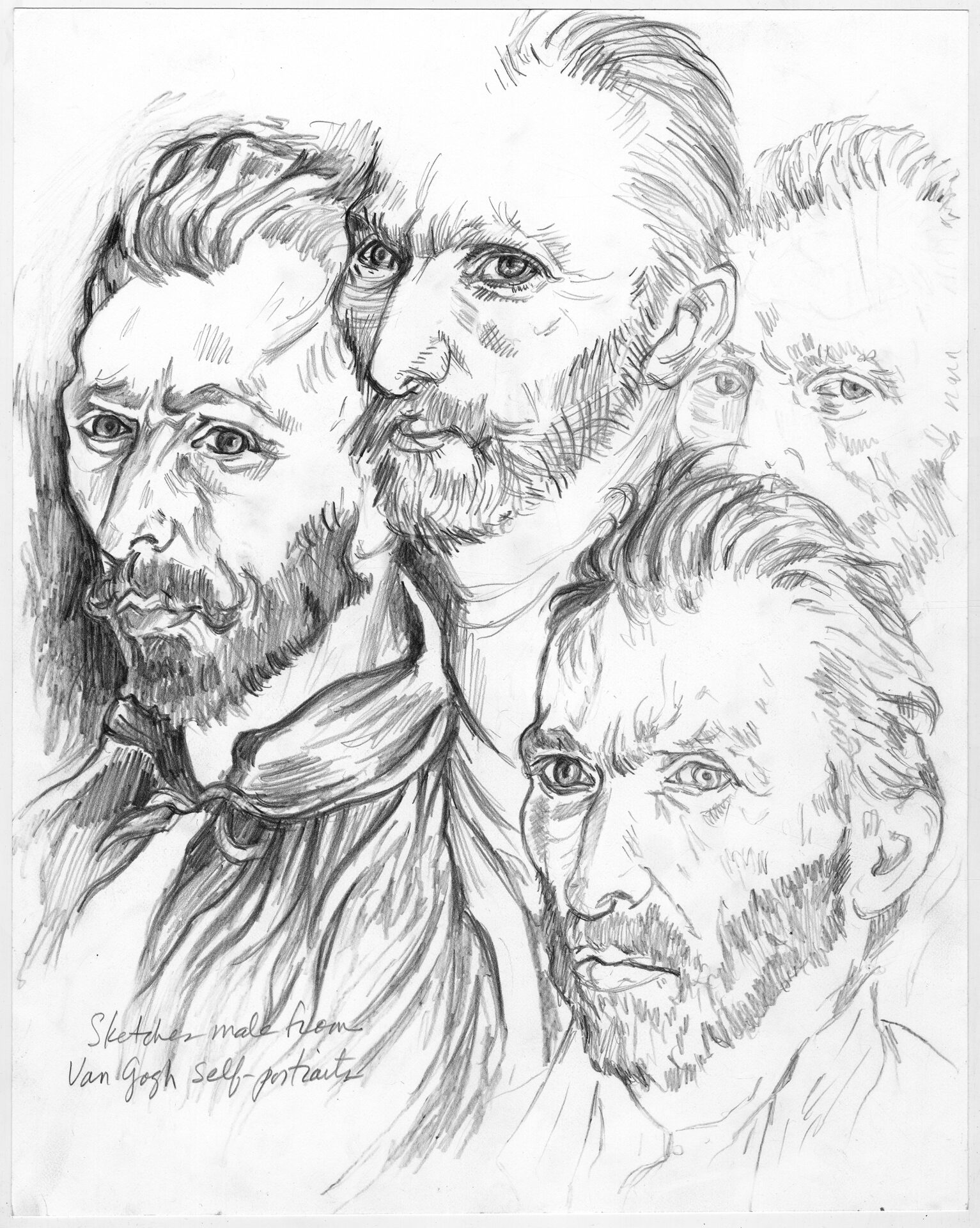

For THE LOST VAN GOGH I went to Amsterdam and spent a lot of time at the Van Gogh Museum. I took my time with the many self-portraits to see how Vincent saw himself in the various stages of his life and moods. He never got very old (he died at 37), but there is a vast difference between his youthful portraits and the later ones, where he often looks tired or troubled, or aged beyond his years. I made my own sketches of his portraits, mimicking his marks and strokes, to understand the way he worked, and it brought me closer to him. The museum offers another gift, one of the artist’s palettes, modestly displayed, along with a few of his brushes and squeezed out tubes of paint, and if that isn’t an experience of Van Gogh, I don’t know what is.

(My sketches based on Van Gogh self-portraits)

At the Rijksmuseum, I spent a long time looking at Rembrandt’s famous painting The Night Watch. Later, when I was writing “The Lost Van Gogh,” I set a scene at the Rijksmuseum and used the painting’s subject matter—civic guardsmen defending their city—to underscore the action and motivation of my characters Luke and John Washington Smith, who are risking their lives in defense of something bigger than themselves. I never use art simply because I want to. It must play an integral part of the scene, of the story, add to it and take it to another level.

Back home, in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, I spent time with their Van Gogh’s Irises, his startling portrait of L’Arlésienne, his fierce painting of sunflowers, and a stirring, swirling self-portrait that I put in my novel, my characters Luke and Alex, so mesmerized by it they don’t know they are being observed just as closely as they observe the painting.

For THE LAST MONA LISA I was lucky enough to be alone in Michelangelo’s Medici Chapel, which is so much smaller than you might imagine, classical, and almost spare, his large sculptures of Dawn and Dusk, Day and Night, almost overwhelming the space. Standing there, quietly, I not only saw but felt what it was about for the first time, and gave my experience to my protagonist Luke, as he stands in the same place, realizing it is a funerary chapel, about the cycle of life, that Michelangelo’s oversize figures are metaphors for life and death, and for the first time understands he his own mortality.

That is what art can do, deepen a moment in the story, give the reader something to think about it, even the desire to go and see the artwork for themself.