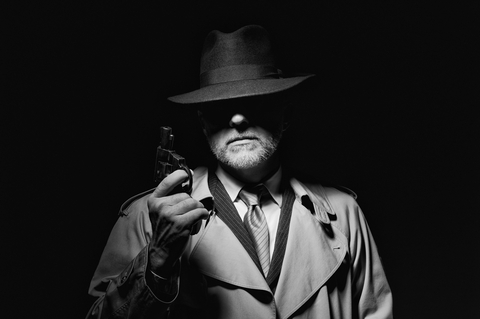

Homefront Spy

By Jack Beaumont

In the espionage thriller genre we’re used to fictional spies who operate as lone wolves with seemingly little integration into the societies they serve. Names that come to mind are James Bond, Ethan Hunt and Jason Bourne.

Let me ruin the fantasy, which I’m the first one to love on a big screen, and tell you what the French external secret service, the DGSE, looks for in a field operative, what we call an OT, or officier traitant. They want someone with mental stability, someone who has something which grounds him back to his real life, to his real identity. An anchor for when he is someone else in the darkness of his mind on the other side of the world. The Company prefers OTs who are married. Kids are a bonus.

The idea of James Bond getting in his front door at the end of a nasty mission and being asked to put out the garbage by his missus, simply makes us laugh. Yet the real people who are put to work in this profession are usually married with kids. Being asked to go out and buy some bread, when you’re still in the grip of post-operation anxiety and paranoia, is a common occurrence for OTs returning home. Going out to buy some milk becomes a war mission.

This domestic situation might make for a more stable and controllable field operative, but it is extraordinarily tough on both spouses, not to mention the kids.

The OT who works in the Operations Directorate of the French DGSE, as I did, has to assume fake IDs and intricate legends and carry these into the field. We have to keep five fictitious IDs alive and active at all times, meaning we have to do our ‘gardening’ on them: posting on LinkedIn, checking our squatter apartments, being seen around the neighbourhood and talking to shopkeepers. We have to ‘become’ these identities, and sometimes the lines blur: a moment comes when you realise you just arrived home and ‘played’ yourself.

When we go into the field under a false identity, all of our real personal effects – watch, phone, wallet, jacket etc. – are kept under lock and key in a safehouse in Paris, and all of our new personal effects are in the name of the fake ID. So, when I’m away under a false ID, there would be no reference in my phone or wallet to my wife, my kids, my address, my neighbourhood or any of my friends or colleagues, or, at least, of the real ones… All those connections are fake and verifiable. This keeps my home life safe should I be caught by another service, but it also creates an absolute moat between my home life and my mission life, meaning my wife and kids can’t contact me and I would never contact them. I’m someone else and this someone else doesn’t know my wife and kids.

So, the very protocols used by intelligence services to keep everyone secure are the same protocols that create alienation and disconnectedness for spies in the field. If you’ve been away for a week, how do you turn up and go straight to a dinner party or a barbecue, smiling easily and making small talk?

It doesn’t work very well in marriages: the wife finds you distant and useless, and the spy can take days to decompress from some of the people and situations he’s just extricated himself from.

On the wife’s side of things, she gets all of the worst of it: a man who suddenly isn’t around for days on end, and when he is around is either a bit distant and exhausted or not behaving like the man she used to know. She can’t talk to friends or family about what her husband does, and she can’t see a psychologist or counsellor. She also has to lie to her loved ones. Entire intelligence services rely on this discretion, and the wives are never thanked or recognised for it.

Wives don’t even get the satisfaction of trapping the terrorist or stopping the shipment of bioweapon precursors. These are important achievements for the spy, given we are not allowed to appear in the newspapers and all of our work is in the ‘Dark Arena.’ An operation that results in success is celebrated by a tight clan of operatives, over a few whiskies in a non-tourist bar, but our wives can’t know about that either.

This creates terrible tension in a spy’s marriage: a paranoid, secretive spy and a wife who is terrified about what might be coming for her kids.

When I first contemplated writing The Frenchman my marriage had survived, but I had PTSD (before I joined the DGSE, I flew special operations missions for the French government, which wasn’t exactly relaxing). My wife had just put up with seven years of me being in the field, in a profession where people usually last five years, and she wanted me to be clear of the French services and cured of the PTSD. She also wanted me to fix the sleep disorder that saw me creeping around the house at night with a knife in my hand.

That’s why I wrote The Frenchman and followed it with Dark Arena. I wanted to get the memories out of my head and in a place I could see them. The fact that the book was taken-up as a novel, and published, was a surprise to me because it was filled with these domestic themes of the intelligence world which I assumed would not be commercial. The fact that the real-life approach is proving popular with readers is very satisfying to me.

One of the few espionage writers who did touch on home life was John le Carré, and he has two sons who have a film and television production company called Ink Factory. It was Ink Factory that bought the rights to make The Frenchman into a show, which, in a funny way, brought my story full-circle and made me feel less like an anomaly.

Don’t get me wrong – spies do some great work. Amid the fatigue, disappointment, and regret is a few moments in your career where you make a difference in the shadows, when things could have gone a different way. I’m proud of what I did to protect people who didn’t even know I exist, but it has taken its toll. A heavy psychological and personal toll.

But it’s the wives who keep the intelligence services running, and I’m glad that I put my wife at the centre of my books. Perhaps she is finally honoured for a role she will never discuss.

Jack Beaumont is the author of The Frenchman and Dark Arena, published by Blackstone Publishing